Figure 1. Folded lines have more surface area than straight lines.

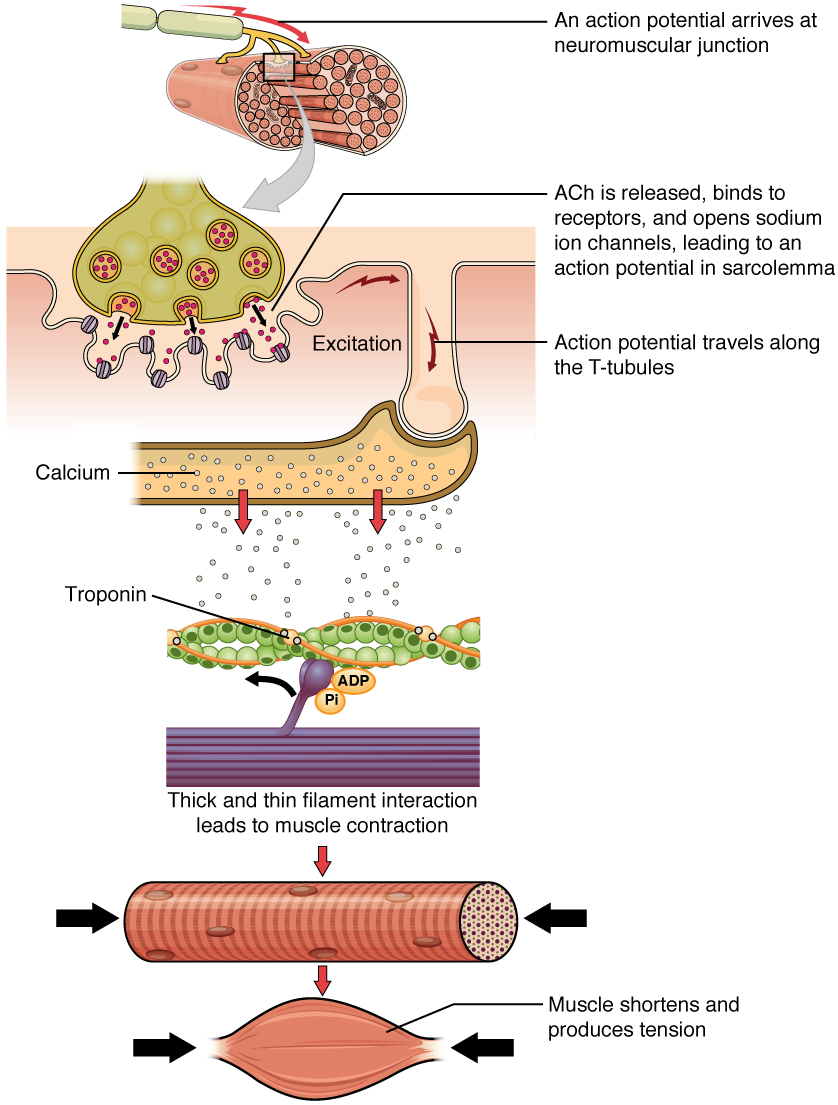

NMJ, Steps of Skeletal Muscle Contraction, Energy Needs and Aging

Anatomy & Physiology I

If you remember back to the beginning of this unit, we talked about the 3 different types of muscle and their controls. Skeletal muscle is voluntarily controlled which means that you cause the movement of your skeletal muscles with thought/intention. We can then infer that the signal to begin a contraction originates from your brain. This signal is electrical in nature and called an action potential. The electricity that powers your computer and flows through the wires of your house is simply energy that is caused by the presence of charged particles. Your body contains many of these charged particles in the form of ions. As a review, remember that muscle cells are said to be polarized meaning that there is a charge difference between the inner and outer face of the cell membrane. This polarization results because of positively charged ions, cations, such as calcium (Ca2+) and sodium (Na+). Inside the cell there are cations, potassium (K+), but the presence of this cation is not enough to overcome the negative charge of the much larger and more common molecules like proteins, etc. Already you can see that the presence of these positively charged particles on either side of the membrane create the opportunity for a charge difference and therefore an electric signal. The electric signal allows voltage gated channels to open. Voltage gated channels are exactly how they sound - the gate opens in response to a particular voltage and closes at a particular voltage. This is important because the positively charged ions that exist on either side of the cell membrane are not at equilibrium, and will diffuse toward the side of the membrane that has fewer of that particular cation when gates are open. Imagine that the ions are claustrophobic. If there are a lot of sodium ions in one particular place they become claustrophobic and desperately want to spread out. When the opportunity presents itself in the form of an open channel the claustrophobic ions seize that opportunity and move from a highly concentrated area to an area with a lower concentration spreading out and easing the claustrophobia. In excitable tissues when voltage gated sodium channels open the sodium ions that were kept outside of the cell begin to flow into the cell diffusing down its concentration gradient. When voltage gated potassium channels open, the potassium inside the cell diffused out of the cell down its gradient. This movement of ions creates a particular type of electricity that we call an action potential. So from here on out when you hear action potential, think electric signal caused because of these cations on either side of the cell membrane that diffuse down their concentration gradients when the opportunity to do so is presented. You will discuss the specifics of an action potential in the nervous system chapter.

Animation 1. View the YouTube animation Sodium and Potassium Gradients (opens in new window)

Now that we understand what an action potential is in theory, we can continue with the steps that precede muscle contraction. We said that the signal to start a contraction comes from the brain. This is because the brain is made out of nervous tissue which, like muscle cells, is excitable and has a polarized membrane. There are some differences between the action potentials we see in nervous and muscular tissue, but the theory is the same.

The brain starts the electrical signal we now know as an action potential. The action potential travels from the brain down a somatic motor neuron until it reaches the skeletal muscle that we are targeting. Remember, soma = body and motor = producing movement, therefore these neurons produce movement/locomotion of the body. The somatic motor neuron branches to stimulate multiple skeletal muscle cells at one time. The junction of these 2 cells – somatic motor neuron and skeletal muscle cell – is called the neuromuscular junction. This presents no mystery as to how the junction got its name. The neuron terminates at the skeletal muscle cells in a bulbous structure called synaptic end bulbs. These bulbs are not directly connected to the skeletal muscle cell the 2 cells are separated by a small gap that is called the synaptic cleft. The signal that traveled down the somatic motor neuron is electrical in nature and if there is a break in an electrical connection, like a broken wire or a synaptic cleft, it is very unsafe for the electricity to arc over that gap. When electricity arcs we cannot be sure of its target and in the body that can be very detrimental. So to resolve this problem when the action potential reaches the end of the somatic motor neuron in the synaptic end bulbs the electrical signal is converted into a chemical one. This chemical signal is safe in the body and will transmit the message to the skeletal muscle on the other side of the synaptic cleft to contract.

Let's examine how this happens. When the action potential reaches the synaptic end bulbs at the end of the axon, the electricity opens voltage gated calcium channels in the membrane of the synaptic end bulb. Calcium, which is in great abundance outside the cell, readily enters the neuron through these open channels. When the calcium enters the neuron it causes vesicles containing the neurotransmitter acetylcholine (ACh) that were being stored in the synaptic end bulbs to undergo exocytosis. This process is where the vesicles merge with the cell membrane of the synaptic end bulb and dump the contents – ACh – into the synaptic cleft. ACh is our chemical signal! We have just seen how the electrical signal triggered a series of events that caused the release of a chemical signal into the cleft, which as we said before is much safer than the electric signal arcing over the cleft.

Animation 2. The Brain Triggers an Action Potential. View the YouTube animation Muscle Excitation Step 1. (opens in new window)

Animation 3. Action Potential Arrives at the Muscle Cell. View the YouTube animation Muscle Excitation Step 2. (opens in new window)

Now that ACh has been released into the synaptic cleft, it will diffuse through the cleft to the surface of the skeletal muscle cell which is called the sarcolemma. The portion of the sarcolemma that faces the synaptic end bulb is folded many times to increase surface area and have more receptors for ACh. This folded portion is called the motor end plate. Remember from previous chapters that the folding increases surface area which in this case is crucial so that you can pack more ACh receptors into this area and will need less ACh to pass the signal along to the muscle that it is now time to contract. Let's draw this out quickly to make sure it is clear. Draw a straight line and a squiggly line up and down. Now add an ACh receptor every centimeter in your drawing. How many receptors did you fit on the straight line versus the folded line?

Figure 1. Folded lines have more surface area than straight lines.

The ACh diffuses through the synaptic cleft and binds to one of the many ACh receptors present on the motor end plate of the sarcolemma. These receptors are also known as ligand-gated sodium channels. This means when the chemical ligand is present (in this case ACh) the channel will open and when ACh is removed, the channel closes. It takes 2 ACh molecules binding to a single ligand gated sodium channel to fully open the channel and allow sodium to diffuse down its concentration from the extracellular fluid into the skeletal muscle cell. Remember from earlier in this chapter sodium is spreading out and moving down its gradient from high to low concentration which is why the sodium enters the muscle cell. Also, remember that sodium is a positively charged ion, Na+, and when this ion moves down its gradient we alter the cell's polarized membrane and cause an action potential in the skeletal muscle cell. We have now converted the chemical signal that was released to protect the body from an arcing electrical signal, back into its electrical form that can travel safely in the skeletal muscle cell along the sarcolemma. The conversion is necessary because the electrical signal will trigger a chain of events and ultimately lead to muscle contraction.

Animation 4. Action Potential activates Voltage-Gated Channels. View the YouTube animation Muscle Excitation Part 3. (opens in new window)

Animation 5. ACh Arrives and Triggers an Action Potential. View the YouTube animation Muscle Excitation Part 4. (opens in new window)

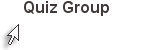

Once the action potential is started in the skeletal muscle cell, it travels along the sarcolemma spreading out across the whole muscle cell which is quite expansive and elongated. The action potential must also spread through the muscle cell to trigger the myofibrils that are not in contact with the sarcolemma to contract with the rest of the cell. To do this the action potential travels along the sarcolemma as it dips down to the interior of the cell along T-tubules (T = transverse). These tubules are invaginations of the sarcolemma, so the signal does not have to be altered to travel into the tubules, it simply spreads out. On either side of the T-tubules are bulges of the sarcoplasmic reticulum, called cisternae, which surround the neighboring sarcomeres. The T-tubule and cisternae of the sarcoplasmic reticulum that it touches on either side form what is known as the triad (since there are 3 components). Therefore, as the signal travels down the T-tubules, the electricity triggers an opening of voltage-gated calcium channels in the sarcoplasmic reticulum. The calcium that is stored in the cisterns of sarcoplasmic reticulum is dumped into the interior of the skeletal muscle cell and sets off a chain of events that we have already discussed.

Figure 2. Narrow T-tubules permit the conduction of electrical impulses. The SR functions to regulate intracellular levels of calcium. Two terminal cisternae (where enlarged SR connects to the T-tubule) and one T-tubule comprise a triad—a "threesome" of membranes, with those of SR on two sides and the T-tubule sandwiched between them.

This process of sending a signal from the brain, across the neuromuscular junction, to cause contraction in the skeletal muscle is known as excitation-contraction coupling. And since we have discussed each section of this so far minus the actual steps of contraction (Sliding Filament Theory) let's summarize it with a series of steps that include the ones we have already mentioned earlier in the chapter.

Side note: creating this big picture in your head can often be the most difficult part of this chapter. I would encourage each of you to read each step and picture it visually in your head as you go through the steps. Do this several times a day for best success. This will help you get that big picture and understand this lengthy process.

Excitation – Contraction Coupling, in summary:

Animation 6. Action Potential Travels the Sarcolemma. View the YouTube animation Muscle Excitation Part 5 (opens in new window).

Place the 5 given steps of excitation – contraction coupling in order or occurrence (not all steps are listed).

Continue your quiz here:

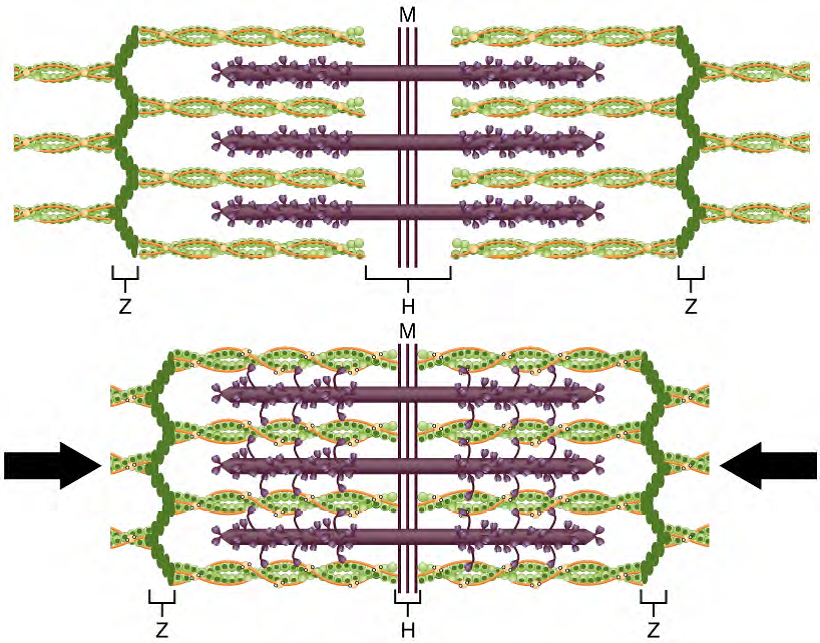

Earlier in the chapter we discussed that when contraction occurs the myosin filaments pull the actin filaments toward the M line of the sarcomere shortening not only the sarcomere but the entire skeletal muscle cell as well. Neither filament changes in length, they simply slide past each other, which is why we refer to the steps of contraction as the Sliding Filament Theory.

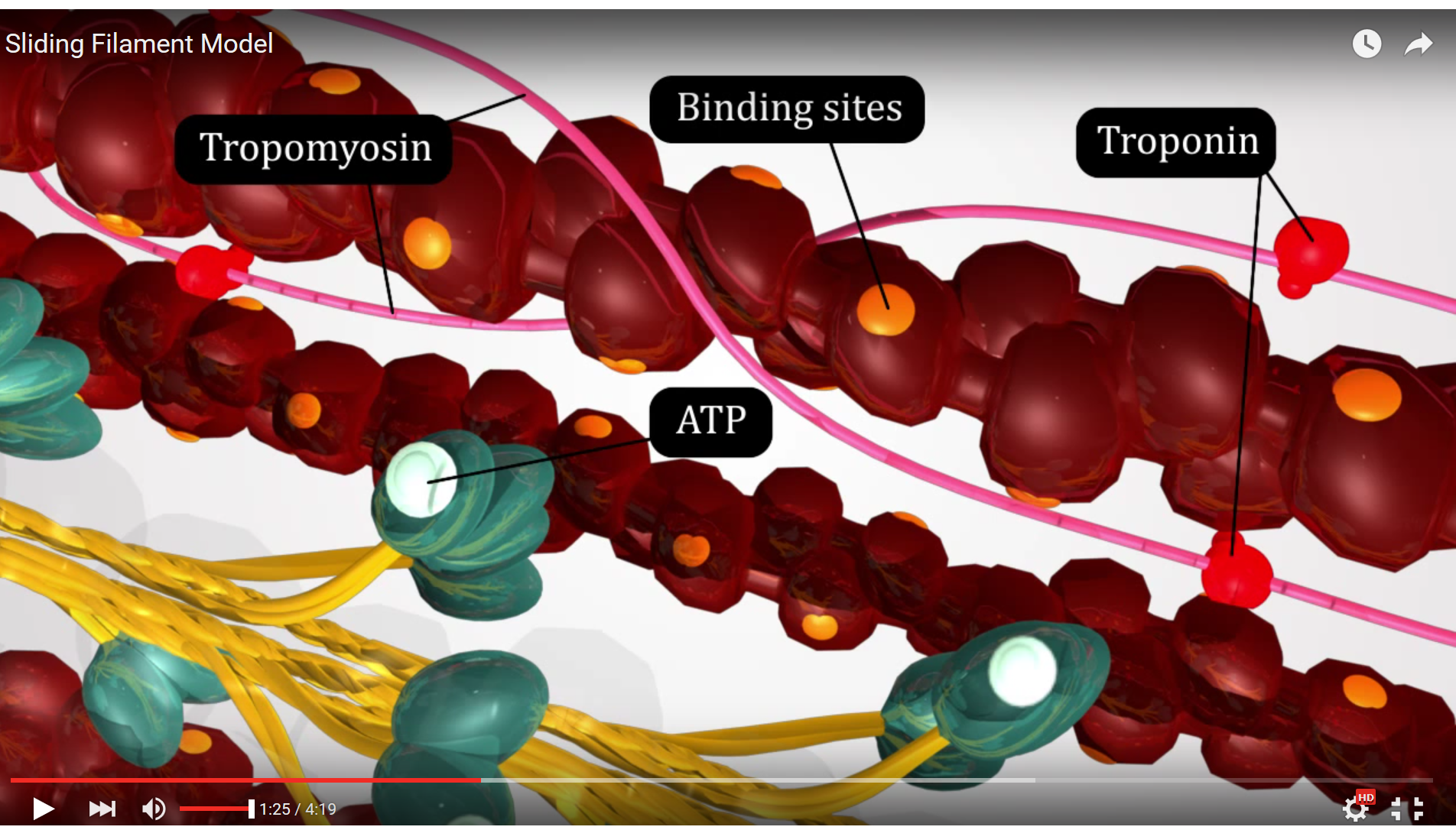

Resuming our excitation - contraction coupling saga, once calcium has been released from the sarcoplasmic reticulum, calcium binds to troponin, tropomyosin is moved out of the way, and actin and myosin can now begin to interact and the Sliding Filament Theory ensues.

Figure 3. This screenshot from the Sliding Filament Model animation shows the landmarks described in the paragraph above.

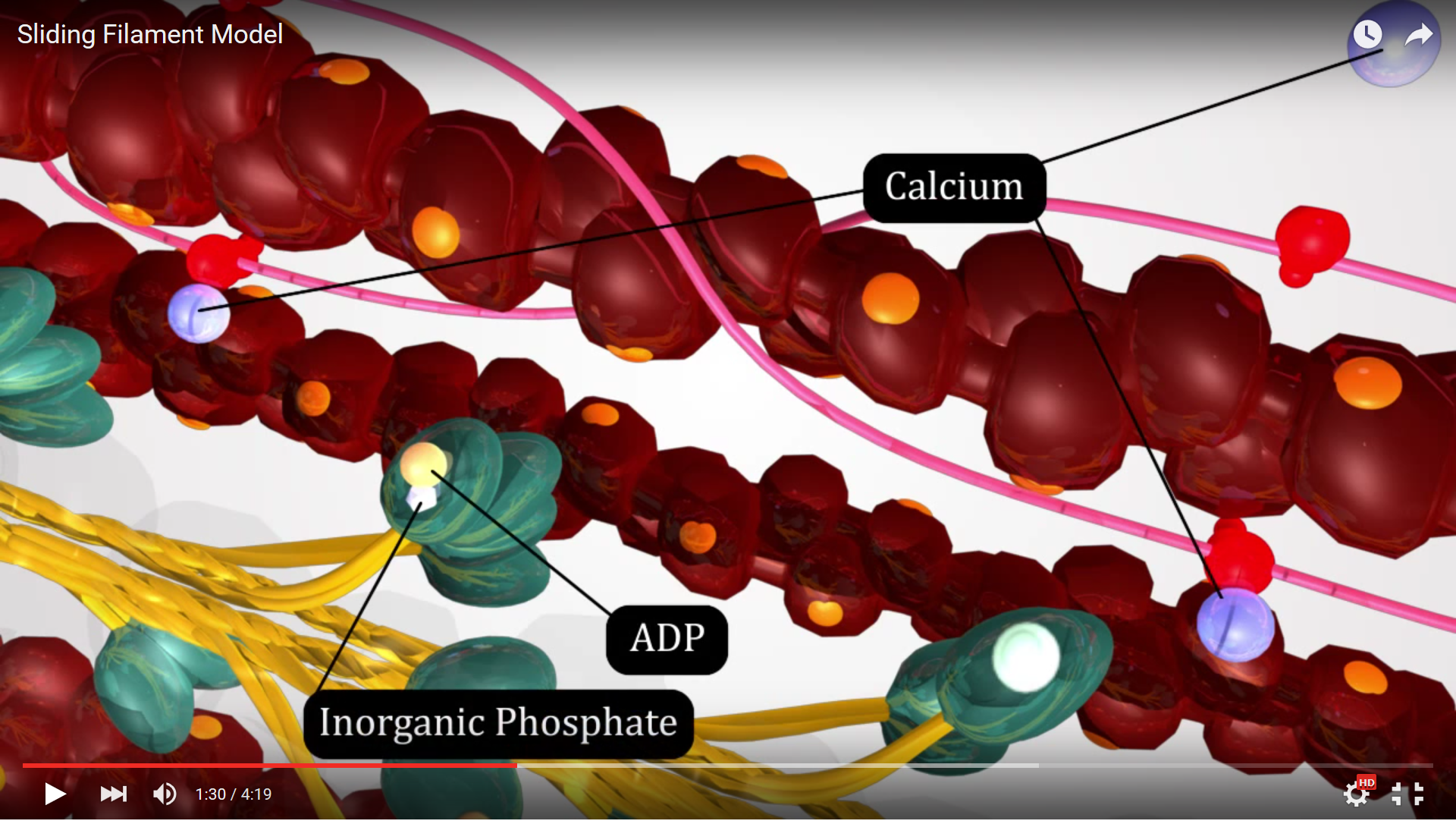

The first step in the Sliding Filament Theory is hydrolysis of ATP on the myosin head by the enzyme ATPase, a portion of the myosin protein that has enzymatic function. The ATP attached to the myosin head is broken down by this enzyme in a hydrolysis reaction, a process utilizing adding water to the ATP breaking the high energy phosphate bond between phosphate groups and forming an ADP and an inorganic phosphate. The energy released by the hydrolysis reaction is harnessed by the myosin filament to distort the hinge region and place the myosin head in alignment with the binding site on the actin filament - this is known as the "ready" or "cocked" position.

Figure 4. This screenshot from the Sliding Filament Model animation shows the landmarks described in the paragraph above.

Now that they are aligned in the ready position, the second step of Sliding Filament Theory can occur which is attachment of the myosin heads to the binding sites on actin. This attachment is commonly known as a cross bridge since the two filaments are joined at this location. The cross bridge produces tension but does not shorten the sarcomere which is our ultimate goal.

To shorten the sarcomere we move on to step 3 of Sliding Filament Theory which is the power stroke. During this step the myosin head releases the inorganic phosphate which changes the conformation of the myosin protein moving the hinge region and causing movement. The power stroke motion is caused when the myosin head changes conformation and moves it pulls the actin toward the M line since as we saw in Sliding Filament Theory step 2 they are connected. Think of this like a spring (representing myosin) and at the end of the spring is where actin would be attached. Step 2 is compressing the spring and step 3 is releasing the spring. This mechanical energy created moves the actin and makes the sarcomere shorter. However, each sarcomere needs to shorten from a varying starting length (varies due to cell type and muscle being studied) to approximately 2.7 um. Each power stroke only shortens the sarcomere 10nm. So many sequential contractions are needed to reach full contraction and produce enough tension to do work. This means that after step 3 has concluded, the myosin head will have to detach from the actin to start the Sliding Filament Theory all over again.

Figure 5. This screenshot from the Sliding Filament Model animation shows the landmarks described in the paragraph above.

Step 4 of the Sliding Filament Theory is detachment of the myosin head from the actin filament. This occurs because the myosin is presented with an ATP molecule from the sarcoplasm and this molecule binds to the active site on the myosin head. The binding of ATP alters myosin's affinity for actin and the two filaments detach from one another. Once they have detached the Sliding Filament Theory can begin all over again...

Figure 6. This screenshot from the Sliding Filament Model animation shows the landmarks described in the paragraph above.

Now view the full animation again, so you can see these steps in action.

Animation 7. View the YouTube animation Sliding Filament Model of Muscle Contration (opens in new window)

In summary, the steps of the SFT are:

The contraction of an individual muscle fiber begins with a signal—the neurotransmitter, ACh—from the motor neuron innervating that fiber. The local membrane of the fiber will depolarize as positively charged sodium ions (Na+) enter, triggering an action potential that spreads to the rest of the membrane will depolarize, including the T-tubules. This triggers the release of calcium ions (Ca++) from storage in the sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR). The Ca++ then initiates contraction, which is sustained by ATP. As long as Ca++ ions remain in the sarcoplasm to bind to troponin, which keeps the actin-binding sites "unshielded," and as long as ATP is available to drive the cross-bridge cycling and the pulling of actin strands by myosin, the muscle fiber will continue to shorten to an anatomical limit.

Figure 7. A cross-bridge forms between actin and the myosin heads triggering contraction. As long as Ca++ ions remain in the sarcoplasm to bind to troponin, and as long as ATP is available, the muscle fiber will continue to shorten.

Muscle contraction usually stops when signaling from the motor neuron ends, which repolarizes the sarcolemma and T-tubules, and closes the voltage-gated calcium channels in the SR. Ca++ ions are then pumped back into the SR, which causes the tropomyosin to or re-cover (close) the binding sites on the actin strands. A muscle also can stop contracting when it runs out of ATP and becomes fatigued

Figure 8. Ca++ ions are pumped back into the SR, which causes the tropomyosin to reshield the binding sites on the actin strands. A muscle may also stop contracting when it runs out of ATP and becomes fatigued.

The order of these steps can be remembered with the mnemonic "Have A Perfect Day" and it can be useful to visualize these steps by imagining rowing a boat. When you sit down in the boat you grab the oars and position them over the water in the "ready" position (step 1). Then you place the oars in the water forming a cross bridge between the oar and the water (step 2). Next is the hard part, pulling the oars (power stroke) through the water to propel your boat forward - sliding over the water (step 3). Lastly, you lift the oars out of the water because one power stroke is not enough to reach your destination (step 4). Energy (new ATP molecule) is used to bring the oars that are in front of you from step 4 to the ready position behind you in step 1 so that you can continue to move across the lake toward your destination.

I do want to clarify that there are several myosin heads protruding from the myosin filament and each head is performing the steps of the Sliding Filament Theory when stimulated by calcium release. So far we have only mentioned one myosin head pulling on the actin filament but there are 20 or more per side of the sarcomere. Each myosin head is operating independently and in a non-synchronized fashion as the other myosin heads. This means that while some myosin heads are in step 2 others are in step 1, 3, and 4. This is useful so that the filaments don't have to start over every time they pass through step 4 of the Sliding Filament Theory. What I mean by this is ... in the game of tug-of-war does everyone on your team let go of the rope at one time to try and grab further down and pull the opposite team toward you? No, each player is operating independently toward the common goal. Some players pull while other release their hands to grab further down the rope, and then the roles become reversed, continuing on until the common goal is reached.

Figure 9. This image illustrates how many myosin heads could be pulling on the actin at one time.

Figure 10. The motions of oars used in a rowboat can be compared to myosin heads in the Sliding Filament Model

Figure 11. The Sliding Filament Model of Muscle Contraction. When a sarcomere contracts, the Z lines move closer together, and the I band becomes smaller. The A band stays the same width. At full contraction, the thin and thick filaments overlap.

The Sliding Filament Theory continues on until maximum contraction has been reached. Now we must turn the contraction off, but how? The first step is for the brain to stop sending action potentials down the somatic motor neuron. This will happen when the brain is satisfied that the work it intended to start has been completed or another stimulus that takes precedence over the current work is received. By stopping the action potentials at the source, the somatic motor neuron stops releasing ACh into the synaptic cleft. This neurotransmitter must be removed so that the ligand gated sodium channel receptors can close preventing further depolarization of the sarcolemma. This removal of ACh can happen in 3 ways. The first is that ACh can simply diffuse away. There are no boundaries or enclosures of the synaptic cleft keeping the ACh in the cleft. This means that ACh following its concentration gradient can simply exit or diffuse out of the cleft. The second method of removal is enzymatic degradation of ACh by the enzyme acetylcholinesterase. This enzyme breaks ACh down into acetate and choline - these products do not bind to the very specific ligand gated channels meaning that when the ACh is broken down it can no longer cause depolarization of the sarcolemma. Then last, the choline component of ACh can be taken back up by the somatic motor neuron removing it from the cleft. Your body recycles everything it can to prevent unnecessary energy expenditure, so this reuptake of the ACh components after the enzyme degrades it not only makes sense but is incredibly efficient.

Once the ACh is no longer available, the sarcolemma stops depolarizing and no more action potentials are created. This means that the channels in the sarcoplasmic reticulum that had originally dumped calcium close and the cell begins using ATP to actively pump the calcium from the sarcoplasm back into the storage facility. Once calcium is removed from troponin, the tropmyosin slides back into place and blocks actin and myosin from attaching - stopping the Sliding Filament Theory in its tracks. Since the myosin heads are no longer holding the actin molecules, the sarcomere then slides apart back to its resting length. Muscle relaxation is essentially our excitation - contraction coupling saga halted at 3 separate steps #1, 6, and 12, all animated below.

Video 8. An Action Potential Starts in the Brain (opens YouTube in new window)

Video 9. ACh Binds to Voltage-Gated Sodium Channel on the Motor End Plate (opens YouTube in new window)

Video 10. Calcium binding to Troponin and the Relaxation of Skeletal Muscle (opens YouTube in new window)

Video 11. Simplification of the Total Excitation Coupling Process (opens YouTube in new window)

1. ACh can simply diffuse away (See note back in Figure 8).

2. Enzymatic degradation of ACh by the enzyme acetylcholinesterase

3. SR Calcium channels are closed; Calcium actively pumped back into the SR

Note that each thick filament of roughly 300 myosin molecules has multiple myosin heads, and many cross-bridges form and break continuously during muscle contraction. Multiply this by all of the sarcomeres in one myofibril, all the myofibrils in one muscle fiber, and all of the muscle fibers in one skeletal muscle, and you can understand why so much energy (ATP) is needed to keep skeletal muscles working. In fact, it is the loss of ATP that results in the rigor mortis observed soon after someone dies. With no further ATP production possible, there is no ATP available for myosin heads to detach from the actin-binding sites, so the cross-bridges stay in place, causing the rigidity in the skeletal muscles.

Every time the sarcomeres contract during the sliding filament mechanism, energy in the form of ATP is required. Review by thinking about which steps needed the ATP….

As you reviewed you could see ATP is required to detach the actin and myosin filaments and to move the myosin head back into the ready position so that another cycle of Sliding Filament can occur. Much like rowing a boat would cause you to expend energy so does this cycle. ATP is also needed to actively pump calcium back into the sarcoplasmic reticulum when contraction has ended so that the muscle can now relax. But where does all of the energy come from?

The amount of ATP that can be stored in the skeletal muscle cell itself is very low because of the chemical stability of ATP and the osmotic contribution of this molecule affecting homeostasis. There is in fact only enough ATP being stored in the skeletal muscle cells to power only a few seconds of activity, 8 muscle twitches to be exact. A muscle twitch is one contraction/relaxation cycle. We often need much more energy than this to sustain a movement to rather than trying to figure out how to store more ATP in the cell, the cell can simply regenerate ATP from its readily available ADP. ADP is adenosine diphosphate and only needs a phosphate group added to it to create adenosine triphosphate which is ATP (2 + 1 = 3 phosphate groups). Therefore, it is much easier and faster to simply regenerate ATP than to work out the logistics of how to store more of it. There are 3 mechanisms that exist in the skeletal muscle cell by which ATP can be regenerated: creatine phosphate metabolism, anaerobic glycolysis/fermentation and aerobic respiration.

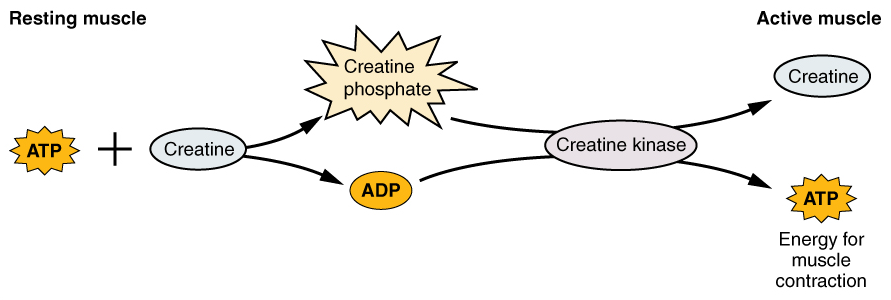

Creatine phosphate is a molecule that can store energy in its phosphate bonds. In a resting muscle, excess ATP transfers its energy to creatine, producing ADP and creatine phosphate. This acts as an energy reserve that can be used to quickly create more ATP. When the muscle starts to contract and needs energy, creatine phosphate transfers its phosphate back to ADP to form ATP and creatine. This reaction is catalyzed by the enzyme creatine kinase and occurs very quickly; thus, creatine phosphate-derived ATP powers the first few seconds of muscle contraction. However, creatine phosphate can only provide approximately 15 seconds worth of energy, at which point another energy source has to be used.

Figure 12. Some ATP is stored in a resting muscle. As contraction starts, it is used up in seconds. More ATP is generated from creatine phosphate for about 15 seconds.

As the ATP produced by creatine phosphate is depleted, muscles turn to glycolysis as an ATP source. Glycolysis is an anaerobic (non-oxygen-dependent) process that breaks down glucose (sugar) to produce ATP; however, glycolysis cannot generate ATP as quickly as creatine phosphate. Thus, the switch to glycolysis results in a slower rate of ATP availability to the muscle. The sugar used in glycolysis can be provided by blood glucose or by metabolizing glycogen that is stored in the muscle. The breakdown of one glucose molecule produces two ATP and two molecules of pyruvic acid, which can be used in aerobic respiration or when oxygen levels are low, converted to lactic acid.

If oxygen is not available, pyruvic acid is converted to lactic acid, which may contribute to muscle fatigue. This occurs during strenuous exercise when high amounts of energy are needed but oxygen cannot be sufficiently delivered to muscle. Glycolysis itself cannot be sustained for very long (approximately 1 minute of muscle activity), but it is useful in facilitating short bursts of high-intensity output. This is because glycolysis does not utilize glucose very efficiently, producing a net gain of two ATPs per molecule of glucose, and the end product of lactic acid, which may contribute to muscle fatigue as it accumulates.

Figure 13. Each glucose molecule produces two ATP and two molecules of pyruvic acid, which can be used in aerobic respiration or converted to lactic acid. If oxygen is not available, pyruvic acid is converted to lactic acid, which may contribute to muscle fatigue. This occurs during strenuous exercise when high amounts of energy are needed but oxygen cannot be sufficiently delivered to muscle.

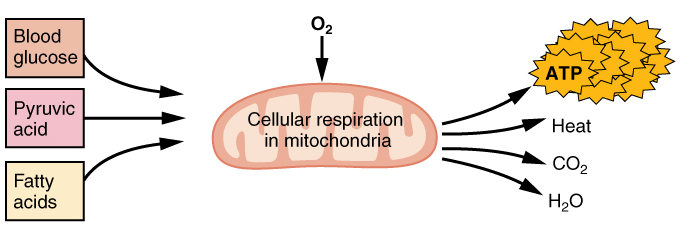

If oxygen is available, pyruvic acid is used in aerobic respiration. Aerobic respiration is the breakdown of glucose or other nutrients in the presence of oxygen (O2) to produce carbon dioxide, water, and ATP. Approximately 95 percent of the ATP required for resting or moderately active muscles is provided by aerobic respiration, which takes place in mitochondria. The inputs for aerobic respiration include glucose circulating in the bloodstream, pyruvic acid, and fatty acids. Aerobic respiration is much more efficient than anaerobic glycolysis, producing approximately 36 ATPs per molecule of glucose versus four from glycolysis. However, aerobic respiration cannot be sustained without a steady supply of O2 to the skeletal muscle and is much slower. To compensate, muscles store small amount of excess oxygen in proteins call myoglobin, allowing for more efficient muscle contractions and less fatigue. Aerobic training also increases the efficiency of the circulatory system so that O2 can be supplied to the muscles for longer periods of time.

Figure 14. Aerobic respiration is the breakdown of glucose in the presence of oxygen (O2) to produce carbon dioxide, water, and ATP. Approximately 95 percent of the ATP required for resting or moderately active muscles is provided by aerobic respiration, which takes place in mitochondria.

Muscle fatigue occurs when a muscle can no longer contract in response to signals from the nervous system. The exact causes of muscle fatigue are not fully known, although certain factors have been correlated with the decreased muscle contraction that occurs during fatigue. ATP is needed for normal muscle contraction, and as ATP reserves are reduced, muscle function may decline. This may be more of a factor in brief, intense muscle output rather than sustained, lower intensity efforts. Lactic acid buildup may lower intracellular pH, affecting enzyme and protein activity. Imbalances in Na+ and K+ levels as a result of membrane depolarization may disrupt Ca2+ flow out of the SR. Long periods of sustained exercise may damage the SR and the sarcolemma, resulting in impaired Ca2+ regulation.

Intense muscle activity results in an oxygen debt, which is the amount of oxygen needed to compensate for ATP produced without oxygen during muscle contraction. Oxygen is required to restore ATP and creatine phosphate levels, convert lactic acid to pyruvic acid, and, in the liver, to convert lactic acid into glucose or glycogen. Other systems used during exercise also require oxygen, and all of these combined processes result in the increased breathing rate that occurs after exercise. Until the oxygen debt has been met, oxygen intake is elevated, even after exercise has stopped (as when you breathe more heavily after climbing even a flight or two of stairs). You can think of oxygen debt like any other debt, i.e. a credit card. If you don't pay your balance on the credit card there are collectors that begin to come after you until you pay or they seize your assets. When you exercise and use a great deal of oxygen you still produce lactic acid in muscles that were unable to get sufficient oxygen. That lactic acid becomes the collector that begins to hound you with fatigue, cramps, or headaches until you bring in enough oxygen to convert that lactic acid into pyruvate. When the lactic acid is gone so is your debt. You can replenish oxygen in various ways such as stretching to increase circulation or even drinking lots of water since H2O has oxygen. Depending on the intensity of the workout it could take hours or days to replenish this debt.

Except where otherwise noted, this work by The Community College Consortium for Bioscience Credentials is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Text from BioBook licensed under CC BY NC SA and Boundless Biology Open Textbook licensed under CC BY SA.

Other text from OpenStaxCollege licensed under CC BY 3.0. Modified by Alice Rudolph, M.A. and Andrea Doub, M.S. for c3bc.

Instructional Design by Courtney A. Harrington, Ph.D., Helen Dollyhite, M.A. and Caroline Smith, M.A. for c3bc.

Media by Brittany Clark, Jordan Campbell, John Reece, Jose DeCastro and Antonio Davis for c3bc.

This product was funded by a grant awarded by the U.S. Department of Labor's Employment and Training Administration. The product was created by the grantee and does not necessarily reflect the official position of the U.S. Department of Labor. The Department of Labor makes no guarantees, warranties, or assurances of any kind, express or implied, with respect to such information, including any information on linked sites and including, but not limited to, accuracy of the information or its completeness, timeliness, usefulness, adequacy, continued availability, or ownership.