Appendicular Skeleton

Anatomy & Physiology I

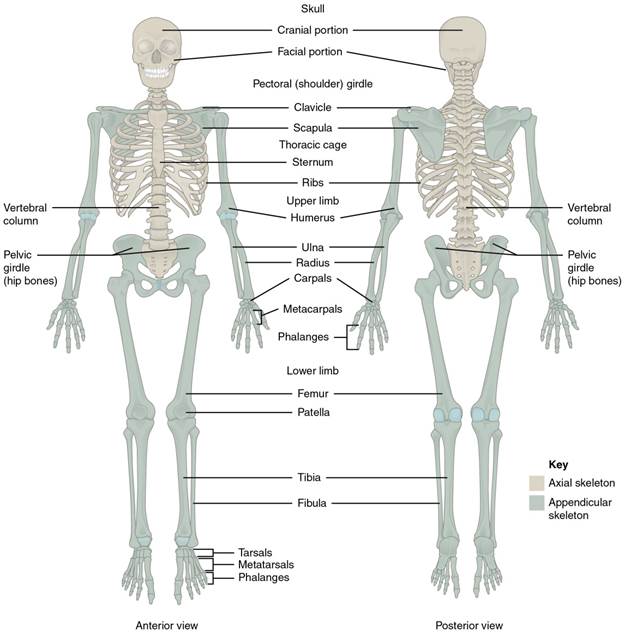

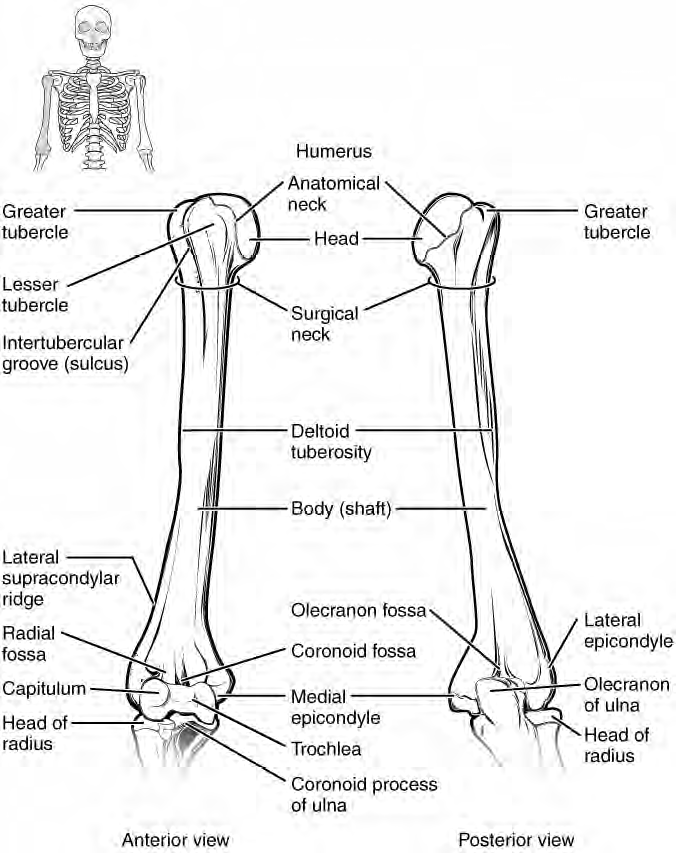

The appendicular skeletal system consists of the bones in the upper and lower appendages as well as those bones that connect them to the axial skeletal system. As you may recall from a previous lesson, the axial skeletal system consists of the main core of the body and includes the skull, thoracic (rib) cage, and vertebral column. The appendicular skeletal system can be subdivided into the pectoral girdle, the bones of the upper extremities, the pelvic girdle and the bones of the lower extremities.

When looking at the bones of the appendicular skeletal system keep in mind that there are two of each of the bones because there are appendages or limbs on both sides of the body. The right bones will be mirror images of the bones on the left. Also, it is helpful to look at the bones in all directions because there are distinct bone markings that you will find on the superior side, inferior side, anterior side, posterior side, lateral side, and medial side of each bone.

Figure 1: The axial skeleton supports the head, neck, back, and chest and thus forms the vertical axis of the body. It consists of the skull, vertebral column (including the sacrum and coccyx), and the thoracic cage, formed by the ribs and sternum, all of which touch the midline of the body or the axis. The appendicular skeleton is made up of all bones of the upper and lower limb, including the girdles that connect them to the axial skeleton.

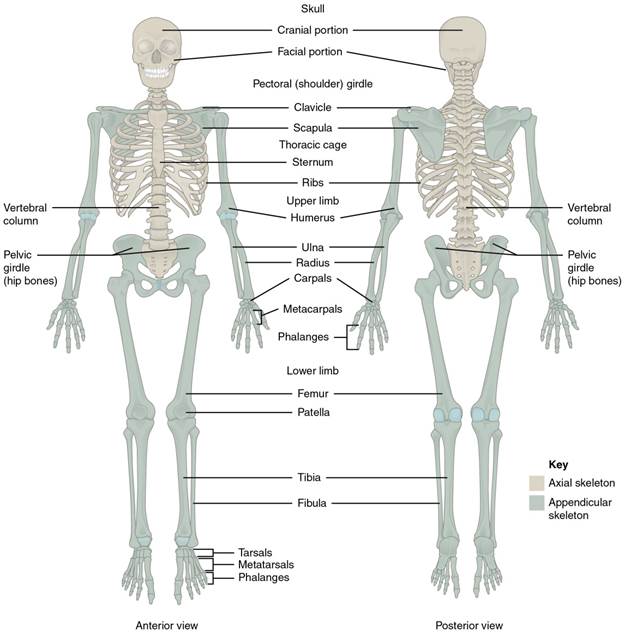

The pectoral girdle consists of two bones, the scapula and clavicle. You can think of these two bones as being the connection between the axial skeleton and the upper arm, although only the clavicle directly connects with the axial skeletal system. The clavicle is located on the anterior side of the skeletal and has an S-shaped appearance to it and has two main connections. One of these connections is with the sternum of the axial system (called the sternal end) and the other connection is to the scapula (called the acromial end). The main purpose of the clavicle is as a support for the arms by holding the arms lateral to the body. If this support is damaged such as in a sports injury or car accident, then the muscles of the arm as well as the weight of the arm will be pulled forward, probably resulting in the person trying to hold the arm back. The most common fracture is in the thinner part of the shaft.

The scapula is what is commonly referred to as the shoulder blade. It is located posteriorly in the body and at a slight angle on the rib cage. It has two main skeletal interactions. One with the clavicle and one with the bone of the arm called the humerus. If looked at by itself, it has a shape of a triangle.

Figure 2: Posterior view of the Pectoral Girdle. The scapula, shaped like a triangle, is attached to the clavicle. The posterior side, seen here, shows the Scapular spine (the ridge across your shoulder blade) that ends superiorly at the acromion process (the point at the top of your shoulder).

On the anterior side superior side you can see the coracoid process (it has a "C" shape to it to help you remember the term has two c's), which is a point of attachment for a shoulder joint ligament. The supraspinous fossa, just posterior to the coracoid process, contains a muscle of a similar name and the subscapular fossa, which also contains a muscle, are seen from the anterior side. From the posterior side of the scapula you can see the acromion, which attaches to the clavicle and narrows at the spine. The spine of the scapula is the prominent ridge on the posterior side of the bone; the shallow depressions on either side of it are named appropriately. It separates the supraspinous fossa from an infraspinous fossa, which also contains a muscle. On the lateral side of the scapula is a shallow depression called the glenoid fossa or cavity, which contains the head of the humerus (the bone of the upper arm) and is part of the shoulder joint (glenohumeral joint). Overall the scapula is important for attachment of muscles especially for rotation at the shoulder that are collectively referred to as the rotator cuff and for connecting to the upper limb via the humerus. The acromioclavicular joint transmits forces from the upper limb to the clavicle. The ligaments around this joint are relatively weak. A hard fall onto the elbow or outstretched hand can stretch or tear the acromioclavicular ligaments, resulting in a moderate injury to the joint.

The following video discusses the pectoral girdle.

Video 1. View the Pectoral Girdle video on YouTube (opens in new window)

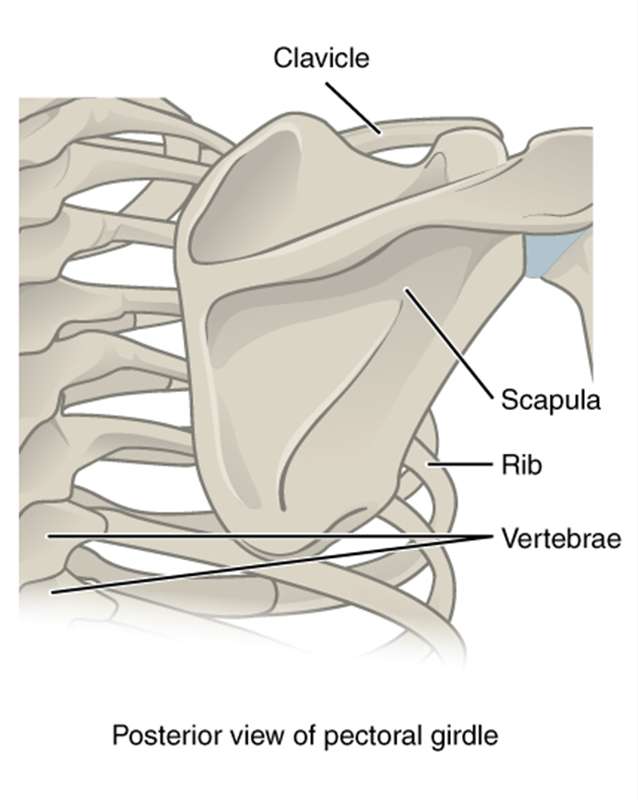

The upper limb consists of the arm, located between the shoulder and elbow joints; the forearm, which is between the elbow and wrist joints; and the hand, which is located distal to the wrist. There are 30 bones in each upper limb. The humerus is the single bone of the upper arm, and the ulna (medially) and the radius (laterally) are the paired bones of the forearm. The base of the hand contains eight bones, each called a carpal bone, and the palm of the hand is formed by five bones, each called a metacarpal bone. The fingers and thumb contain a total of 14 bones, each of which is a phalanx bone of the hand.

Figure 3. Humerus or upper arm bone. Both the right and left humerus bones are shown. Notice the proximal end's head of the humerus, the surgical neck (easier to cut or break than the anatomical neck), the greater tubercle on the lateral side, the deltoid tuberosity, the olecranon fossa, the lateral and medial epicondyles and the distal condyle (has two parts: trochlea and capitulum).

There is one bone in the arm region called the humerus. The humerus is a long bone that has two distinct bulbous ends called the epiphyses and a middle region generally called the diaphysis. At the proximal epiphysis, is a rounded ball shaped area called the head of the humerus. This feature fits in with the glenoid cavity of the scapula and is one part of what is called the shoulder joint. Next to the head of the humerus is the anatomical neck. Located on the lateral side of the proximal epiphysis is an expanded area called the greater tubercle and a smaller lesser tubercle that are separated from each other by the intertubercular groove. Both the greater tubercle and lesser tubercle are attachment points for muscles that act across the shoulder joint. The surgical neck is located at the base of the proximal epiphysis and attaches to the diaphysis. The surgical neck is commonly a site of arm fractures. On the diaphysis, is a roughed area called the deltoid tuberosity, which is a site of attachment for a muscle called the deltoid. On the distal epiphysis of the humerus is located a condyle. This condyle is divided up into two parts. The medial part of the condyle is called the trochlea, this is a pulley-shaped region which articulates with the trochlear notch of the ulna. The lateral part of the condyle is the capitulum, a rounded, knob-like structure that articulates with the radius bone. On the posterior distal epiphysis, is a deep depression called olecranon fossa that receives the olecranon process of the ulna and allows movement at the elbow joint as the arm extends.

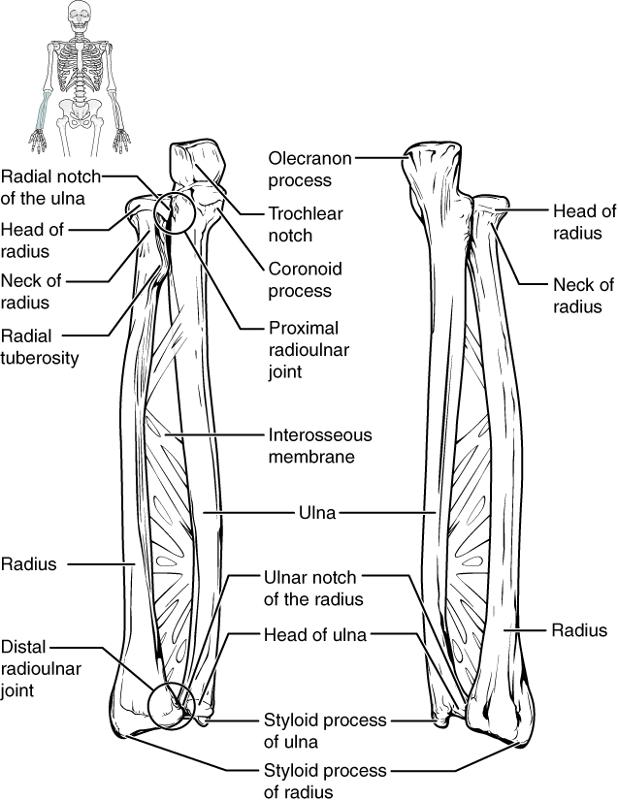

Figure 4. Ulna and radius of the lower arm.

The ulna is located on the medial side of the forearm, and the radius is on the lateral side. These bones are attached to each other by an interosseous membrane.On the ulna several landmarks (bone markings) are noticeable. The olecranon process that fits into the fossa on the humerus is our elbow. The trochlea of the humerus fits into the trochlear notch on the proximal side of the ulna, as well. The head of the radius is lateral to the ulna's coronoid process. On the radius make note of the radial tuberosity, since the biceps tendon inserts at this point (seen later in the muscles).

Carpals, Metacarpals, and Phalanx Bones (plural phalanges)

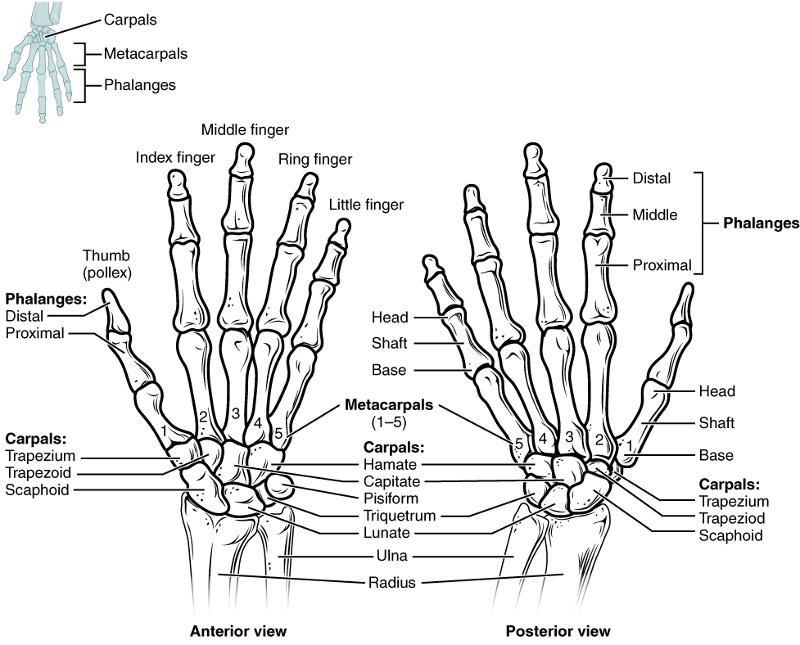

Figure 5. The wrist consists of eight carpal bones that are arranged in two rows. The carpal bones form the base of the hand. Three of these carpal bones articulate with radius. The ulna does not directly articulate with any of the carpal bones. The distal carpal bones articulate with each other and along with the carpals that articulate with the radius contribute to the movement of the hand at the wrist. The distal carpal bones also articulate with the metacarpal bones of the hand.

The main part of the hand consists of 5 metacarpal bones. These bones connect with the carpal bones as well as with phalanges of the fingers and thumbs. The proximal end of the each metacarpal bone articulates with one of the distal carpal bones. Each of these articulations is a carpometacarpal joint. The expanded distal end of each metacarpal bone articulates at the metacarpophalangeal joint with the proximal phalanx bone of the thumb or one of the fingers. The distal end also forms the knuckles of the hand, at the base of the fingers. The metacarpal bones are numbered 1-5 beginning at the thumb. The first metacarpal has greater flexibility than the other metacarpals, which allows us to grip objects with opposable thumbs.

The fingers and thumbs are made up of 14 bones each of which are called a phalanx. The plural form of phalanx is called phalanges. The phalanges are identified by their location. Each finger and thumb contain a proximal phalanx that articulates with a metacarpal bone. Each finger but not the thumb contains a middle phalanx. The fingers and thumb also contain distal phalanges. Therefore the fingers contain three phalanges each and the thumb contains two phalanges each.

Figure 6. In the articulated hand, the carpal bones form a U-shaped grouping. A strong ligament called the flexor retinaculum spans the top of this U-shaped area to maintain this grouping of the carpal bones. Together the carpal bones and the flexor retinaculum form a passageway called the carpal tunnel, with the carpal bones forming the walls and floor, and the flexor retinaculum forming the roof of this space. The tendons of nine muscles of the anterior forearm and a nerve pass through this narrow tunnel to enter the hand.

The carpal bones form a U-shape and a strong ligament called the flexor retinaculum spans the top of this U-shaped area to secure the carpal bones. Together the carpal bones and the flexor retinaculum form a passageway called the carpal tunnel. Overuse of the muscle tendons or wrist injury can produce inflammation and swelling within this space. This produces compression of the nerve, resulting in carpal tunnel syndrome, which is characterized by pain or numbness, and muscle weakness in those areas of the hand supplied by this nerve.

Figure 7. Bones of the Pelvic Girdle. [from openstax] The pelvic girdle is formed by the os coxae or hip bones. The hip bone attaches the lower limb to the axial skeleton through its articulation with the sacrum. The right and left hip bones, plus the sacrum and the coccyx, together form the pelvis.

The pelvic girdle consists of two bones called coxal bones. These bones serve as attachments for the lower limbs and to the axial skeleton through the sacrum. The two coxal bones are also attached to each other anteriorly. The bony pelvis is the entire structure formed by the two hip bones, the sacrum, and attached inferiorly to the sacrum, the coccyx. Unlike the bones of the pectoral girdle, which are highly mobile to enhance the range of upper limbe movements the bones of the pelvis are strongly united.

Unlike the bones of the pectoral girdle, which are highly mobile to enhance the range of upper limb movements, the bones of the pelvis are strongly united to each other to form a largely immobile, weight bearing structure. This is important for stability because it enables the weight of the body to be easily transferred laterally from the vertebral column, through the pelvic girdle and hip joints, and into either the lower limb lower limb whenever the other limb is not bearing weight. Thus, the immobility of the pelvis provides a strong foundation for the upper body as it rests on top of the mobile lower limbs.

The coxal bones are actually three bones that are fused into one structure. These three bones are called the ilium, ischium, and pubis. The superior part of the coxal bones is the flared part called the ilium. The ilium is connected to the sacrum in the posterior part of the hip called the sacroiliac joint. The inferior part of the coxal bone is composed of two bones, the ischium and the pubis. The ischium forms the posterior part of the inferior portion of the coxal bone. The pubis forms the anterior part of the inferior part of the coxal bone and is connected to each other at a joint called the pubic symphysis (symphysis pubis).

Ilium

The superior border of the ilium is the iliac crest that rounds to two iliac spines, which serve as attachment points for muscles. On the posterior margin is a U-shaped greater sciatic notch through which a nerve called the sciatic nerve passes.

Ischium

The ischium is the posterior inferior part of the coxal bone. The large, roughened area of the inferior ischium is the ischial tuberosity. This serves as the attachment for the posterior thigh muscles and also carries the weight of the body when sitting. You might think of this feature as the sitting bone. Another feature of the ischium is the ischial spine. This is a bony projection that separates two sciatic notches.

Pubis

This forms the anterior part of the inferior part of the pelvis. The pubic bones the two coxal bones are connected to each other through a joint called the pubic symphysis, which is slightly moveable but becomes more moveable during labor at the end of a pregnancy. When the pubic bones are connected to each other, you should also be able to detect an angle beneath the bones called the pubic arch or the pubic angle. The degree of the pubic arch differs depending on sex and is a useful indicator in forensics for determining whether a skeleton is male or female, as much of the difference between males and females is the structure of the pelvis as will be explained shortly.

Several features of the pelvis are formed from the fusion of all three bones or are best seen when the whole pelvis is put together. One of these features is a deep socket called the acetabulum. This is the articulation for the head of the femur and is considered one part of the hip joint. On the anteriorinferior is the obturator foramen. This opening contains connective tissue and muscles.

Spaces within the pelvis are divided into the greater pelvis (false pelvis) and the lesser pelvis (true pelvis). The greater pelvis encases some of the lower abdominal organs and extends from one ilium to the next ilium. The true pelvis is bordered by the pelvic brim and contains two openings. The opening into the true pelvis is called the pelvic inlet and the opening out of the true pelvis called the pelvic outlet.

|

Figure 8. Female Pelvis |

Figure 9. Male Pelvis |

| Differences Between the Female and Male Pelvis | Female pelvis | Male pelvis |

|---|---|---|

| Pelvic weight | Bones of the pelvis are lighter and thinner | Bones of the pelvis are thicker and heavier |

| Pelvic inlet shape | Pelvic inlet has a round or oval shape | Pelvic inlet is heart-shaped |

| Lesser pelvic cavity shape | Lesser pelvic cavity is shorter and wider | Lesser pelvic cavity is longer and narrower |

| Pelvic arch | Pelvic arch is greater than 100 degrees | Pelvic arch is less than 90 degrees |

| Pelvic outlet shape | Pelvic outlet is rounded and larger | Pelvic outlet is smaller |

|

Greater Sciatic Notch |

Almost a 90 degree angle |

More narrow |

In general the major differences between the male and female pelvis, concern the female pelvis necessity of being wide enough for a baby to pass through. Therefore the female pelvis tends to be wider in both the pelvic inlet and pelvic outlet and tends to have a wide pubic arch of a 100 degrees or more where the male pelvis tends to be thicker because of the generally more muscular aspect of the male and has a pubic arch of less than 90 degrees.

The bones of the lower limbs include the femur, the tibia, the tarsals, metatarsals, and phalanges. Except for the tarsals, all of the bones of the lower limbs consist of long bones that have two distinct ends (epiphyses) and a shaft region called a diaphysis.

Femur

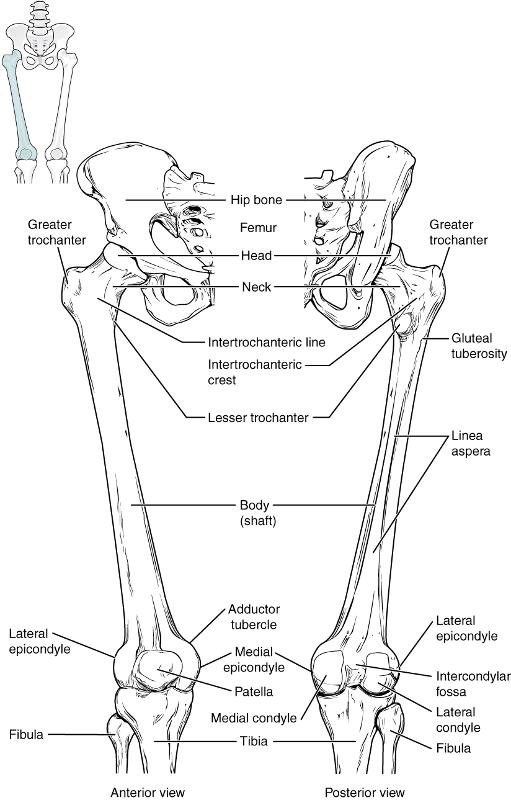

Figure 10. The bone of the thigh is called the femur. This is the longest bone and strongest bone of the body because of its need to hold up the entire weight of the body. This bone articulates with the acetabulum of the pelvis at its proximal end and the tibia at its distal end. It is often a site of many hip fractures. Several parts of the femur include the ball-shaped head, which articulates with the acetabulum and also include a small depression called the fovea capitis, which contains a ligament that helps to attach it to the acetabulum. Laterally next to the head are two large projections: the greater trochanters and lesser trochanters. These projections are attachments points for muscles or ligaments. The head is attached to the shaft of the bone by a neck. Along the shaft on the posterior side is the linea aspera, that is a site of attachment for the gluteal muscles. At the distal end of the femur are two condyles that articulate with the major bone of the lower leg called the tibia. Next to each of these condyles are epicondyles that provide attachment points for ligaments and tendons. Also articulating with the femur is the patella, which is a round-shaped bone that develops after birth and helps to provide leverage to the knee joint eventually helping the individual to walk.

Patella

The patella is a round (sesamoid) bone that is located inside of tendon. This tendon extends from the quadriceps muscle and attaches to the tibial tuberosity on the tibia. The patella helps to prevent this tendon from rubbing against the surface of the femur and also increases leverage during walking.

Tibia

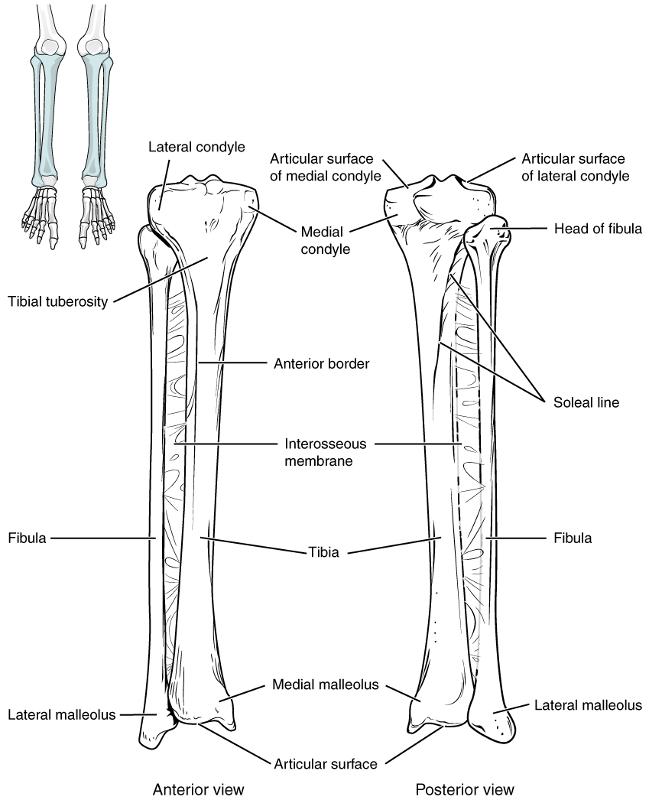

Figure 11. This is the medial bone of the lower leg. Of the two bones in the lower leg, the tibia bears most of the weight coming from the femur. At the proximal end of the tibia are two condyles that also articulate with the condyles of the femur. Below the condyles is a rough process called the tibial tuberosity. This process is a site of attachment for a tendon that connects the tibia with the patella and is a major ligament associated with the knee joint. Along the anterior side of the tibia is the anterior crest, which can be felt underneath the skin as a ridge. At the distal side on the medial side is the medial malleolus, which is large bony bump that is often thought of as the inner ankle.

Fibula

This is the lateral bone of the lower leg. In comparison with the tibia, the fibula is thinner and is not suitable for weight bearing. It is mostly for the attachment of various muscles and ligaments. At the proximal end of the fibula is the head of the fibula. his is a knobby structure that articulates with the proximal, lateral end of the tibia at the lateral condyle of the tibia. At the opposite end of the fibula is the lateral malleolus. This is a process that is easily felt on the lateral side of the ankle region. Along with the medial malleolus of the tibia, the lateral malleolus articulates with a large tarsal bone called the talus, which anchors the lower leg with the ankle and foot.

The tarsal bones form the posterior part of the foot. They are made up of seven short bones. While each of these bones have individual names, the two largest are important to know by their individual names. The tarsal bone that articulates with the leg is called the talus. The largest of the tarsal bones that is inferior to the talus and is commonly referred to as the heel bone is the calcaneous. The talus transfers the weight from the tibia to the calcaneous.

Metatarsal Bones

Like with the hand there are five long bones in the anterior part of the foot called metatarsals. These are distinguished from each other by their number (1-5) starting with the medial side of the foot and preceding toward the lateral side of the foot. The metatarsals articulate with the tarsals at their proximal ends and the phalanges of the foot at their distal end.

Phalanges

The toes contain 14 bones called phalanges. They are identified in a similar manner as the phalanges of the fingers. Each toes has three phalanges (proximal, middle, and distal) except for the big toe (hallux) that has two phalanges (proximal and distal).

Arches in the Foot

When the foot comes into contact with the ground during walking, running, or jumping activities, the impact of the body weight puts a tremendous amount of pressure and force on the foot. During running, the force applied to each foot as it contacts the ground can be up to 2.5 times your body weight. The bones, joints, ligaments, and muscles of the foot absorb this force, thus greatly reducing the amount of shock that is passed superiorly into the lower limb and body. The arches of the foot play an important role in this shock-absorbing ability. When weight is applied to the foot, these arches will flatten somewhat, thus absorbing energy. When the weight is removed, the arch rebounds, giving "spring" to the step. The arches also serve to distribute body weight side to side and to either end of the foot.

Except where otherwise noted, this work by The Community College Consortium for Bioscience Credentials is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Text from BioBook licensed under CC BY NC SA and Boundless Biology Open Textbook licensed under CC BY SA.

Other text from OpenStaxCollege licensed under CC BY 3.0. Modified by Alice Rudolph, M.A. and Amy Bauguess, M.S.for c3bc.

Instructional Design by Courtney A. Harrington, Ph.D., Helen Dollyhite, M.A. and Caroline Smith, M.A. for c3bc

Media by Brittany Clark, Lucious Oliver, II, John Reece and Antonio Davis for c3bc.

This product was funded by a grant awarded by the U.S. Department of Labor's Employment and Training Administration. The product was created by the grantee and does not necessarily reflect the official position of the U.S. Department of Labor. The Department of Labor makes no guarantees, warranties, or assurances of any kind, express or implied, with respect to such information, including any information on linked sites and including, but not limited to, accuracy of the information or its completeness, timeliness, usefulness, adequacy, continued availability, or ownership.

;