(b)

(b)

Structure and Function of the Skin

Integumentary System

Our skin: we cherish it and worship its beauty, but take it for granted and misunderstand its importance for providing much of our needs. The integumentary system refers to the skin and its accessory structures, and it is responsible for much more than simply lending to your outward appearance. In the adult human body, the skin makes up about 16 percent of body weight and covers an area of 1.5 to 2m2. In fact, the skin and accessory structures are the largest organ system in the human body. It protects your inner organs, regulates your temperature and protects you from foreign invaders among other things, so you should keep it healthy. In addition to the structure and function of this large organ, the skin, you should be familiar with some of the diseases, disorders, and injuries that can affect this system.

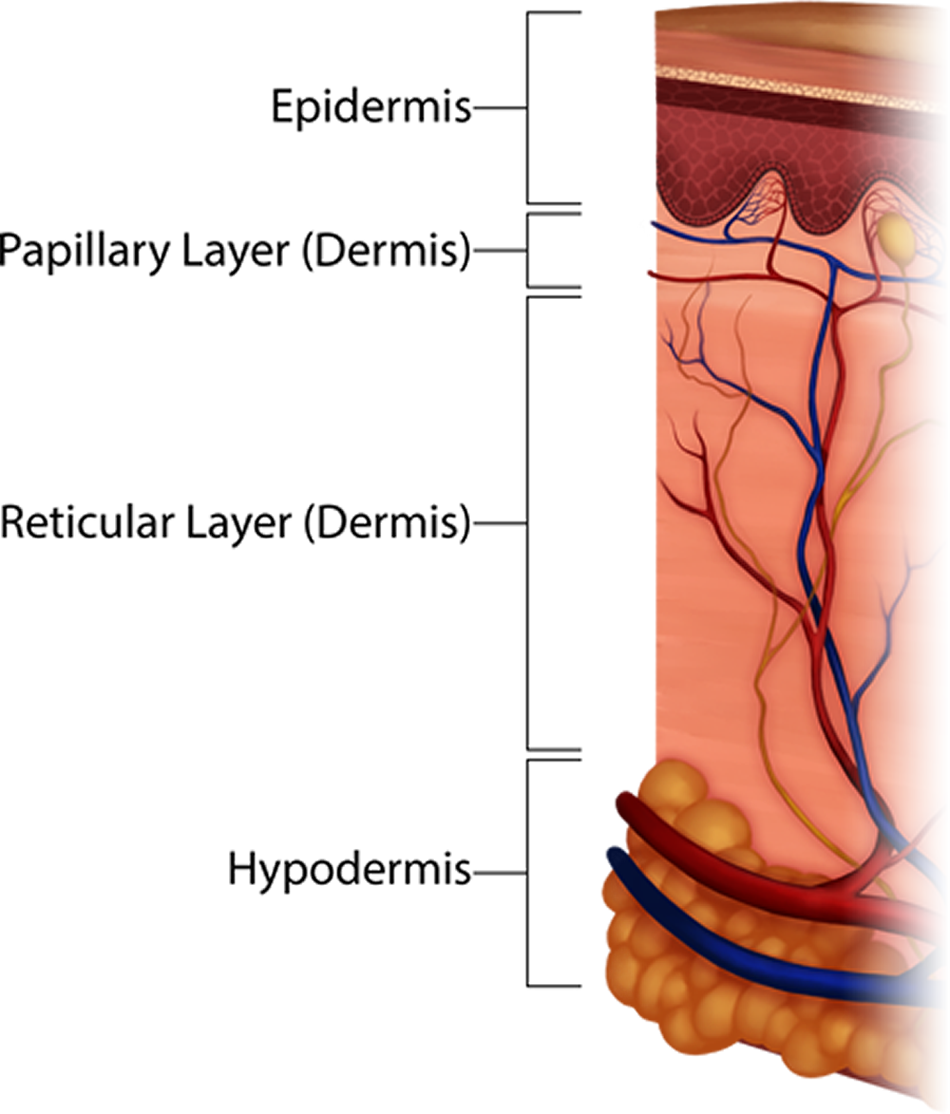

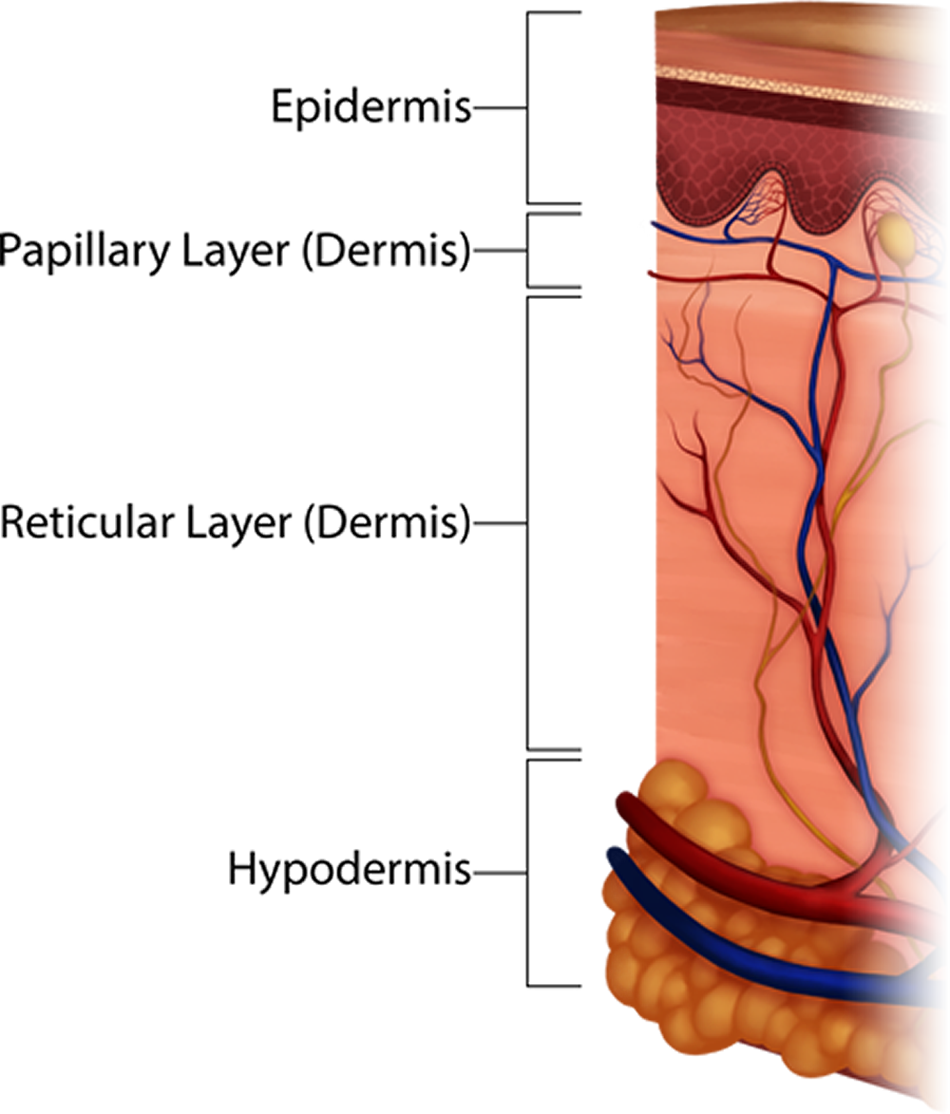

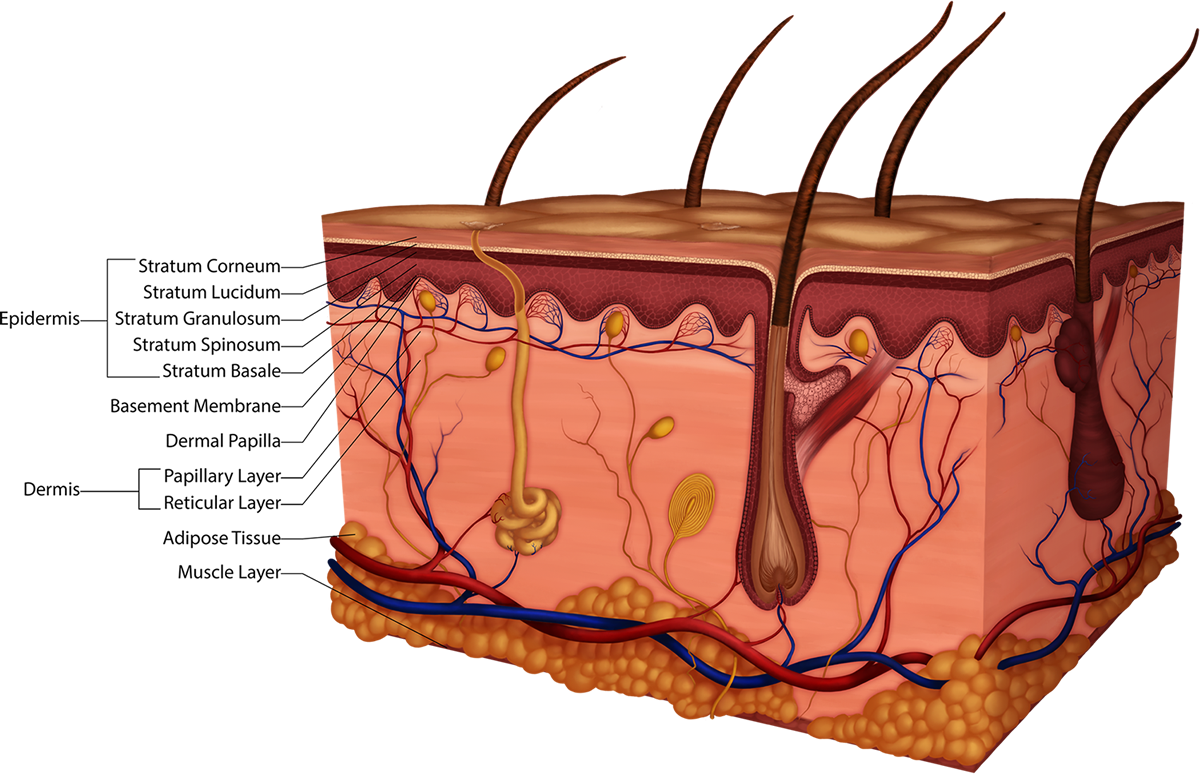

This organ we call the skin (Figure 1) consists of two primary layers, the thinner, superficial epidermis and the thicker, deeper dermis (epi - upon or above; derma - skin). There is a third layer deep to the dermis called the hypodermis, but it is not technically part of the skin, also called the cutaneous membrane. The hypodermis is where we get the term hypodermic needle, which is obviously inserted " under " the dermis or skin. The hypodermis is also called the subcutaneous layer (you've heard of giving a shot " sub-Q ", this is where that term comes from- "subcu" or under the cutaneous membrane or skin).

(a) (b)

(b)

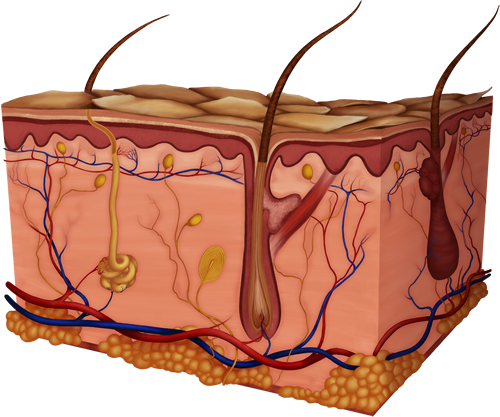

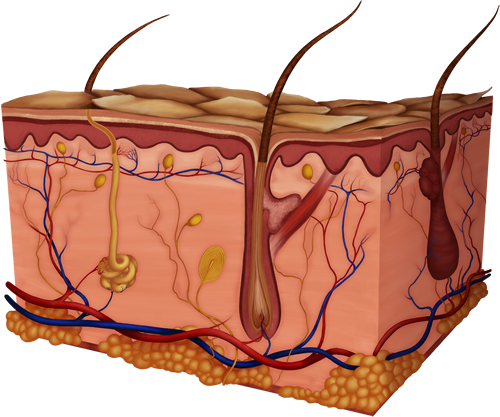

Figure 1. C ross-Sections illustrating skin layers: (a) is a smaller cross-section with the layers of skin (epidermis, the two layers of the dermis- papillary and reticular, and hypodermis) labeled; while (b) is a larger cross-section of skin and many of its internal structures. In this diagram you can tell that the epidermis is thin (shown in the darker colored layers at the top and only about 0.1mm deep!) and the dermis contains most of the skin's organs. The hypodermis is shown beneath the dermis, and is made of adipose tissue resembling groups of yellow balls.

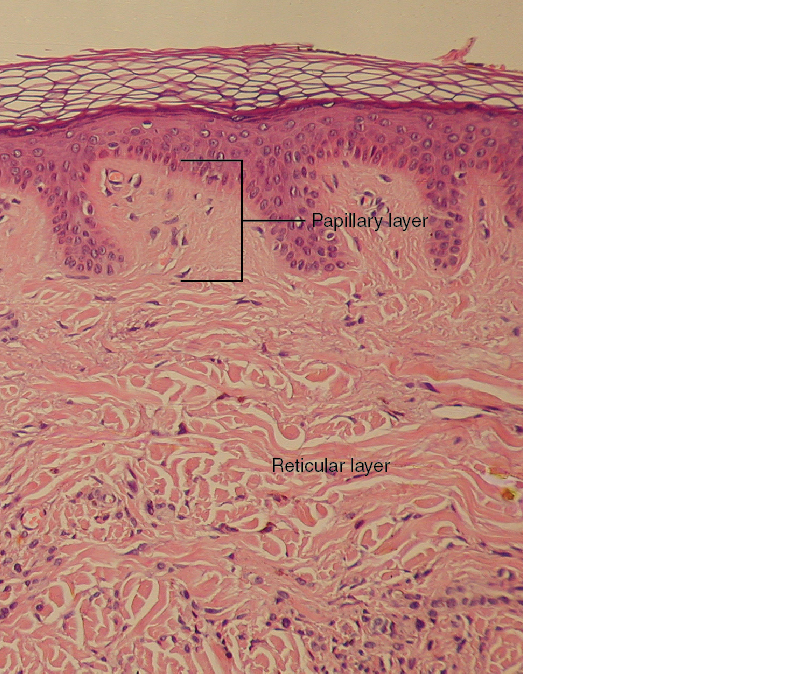

Notice in the figure below that the surface layer, the epidermis, is not filled with blood vessels, or vascularized, at all. This serves a vital protective function for the body since the epidermis is commonly injured from even the simplest of daily activities. Imagine if the epidermis was vascularized, every paper cut could open a blood vessel and cause you to bleed profusely. The dermis, the deeper layer of skin, is well vascularized (has numerous blood vessels). This is important to not only receive nutrients but to place them in close enough proximity to allow nutrients to diffuse to the epidermis. Those cells stay alive even though it has no blood vessels of its own. Notice, also, the many nervous receptors in the skin, too, which keep communication lines open to the brain and provide information about our external environment.

Figure 2. Parts of the Epidermis and the Dermis: Epidermal layers are the Stratum Corneum, Stratum Lucidum (only in thick skin), Stratum Granulosum, Stratum Spinosum and Stratum Basale (ba-sal-ee). The dermis has the superior papillary layer and the deeper reticular layer. Adipose is under these two layers of the skin and muscle is seen under that.

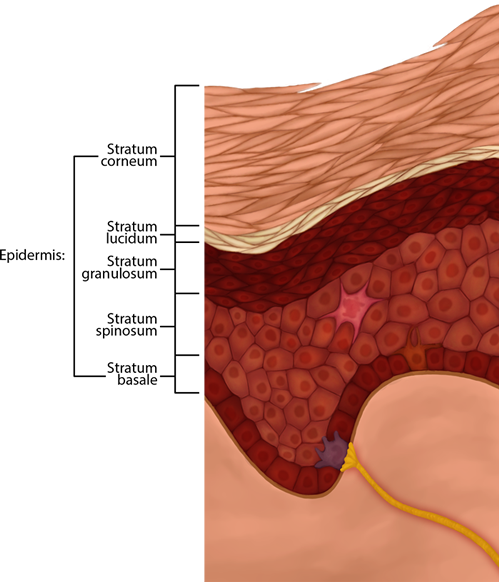

The epidermis is a stratified squamous epithelial tissue that has cells called keratinocytes, which are cells that eventually produce a very durable protein, keratin. Keratin is a water repellant protein that saturates the cells as they apporach the top layer, the corneum. Keratinization increases in the cells from deep to superficial, starting in the middle epidermal layer called stratum granulosum. The keratin protein is akin to the wax used on your car. Just like the wax, the protein repels water causing it to bead on the surface; however, your skin and the wax are not waterproof. If you soak in the tub initially water will bead on your skin, but eventually the epidermis will saturate and wrinkle or prune.

Figure 3. Micrographic Representation of the Epidermal Skin Layers Described Below

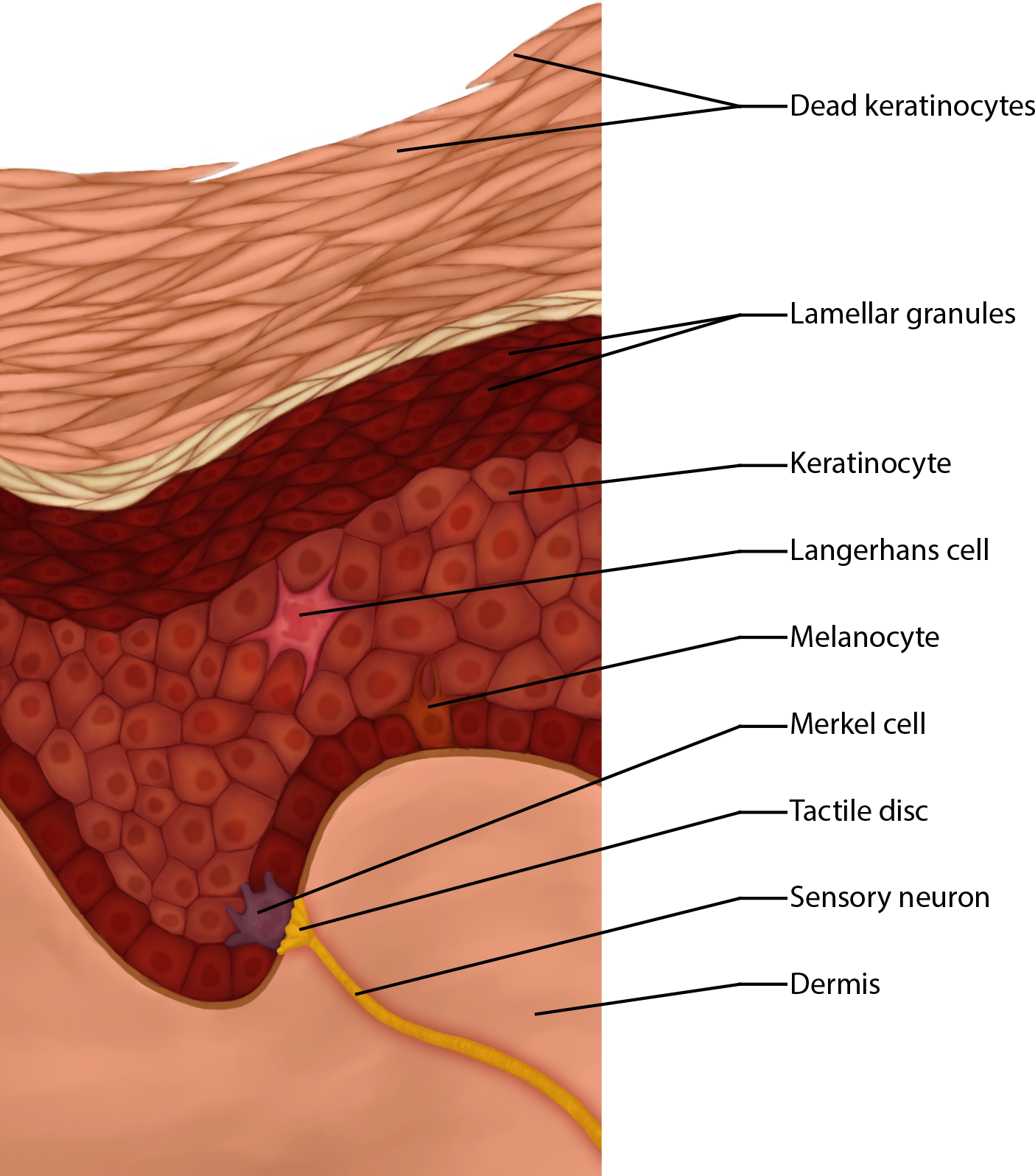

Figure 4. Specialized Epidermal Cell include Langerhans Cells for immune function, melanocytes, Merkel cells, and tactile discs.

Video 1. View the Epidermis video on YouTube (opens in new window)

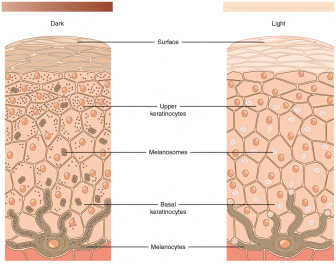

Think About This: If the number of melanocytes is the same in people of all ethnic backgrounds, what causes their skin color to differ?

Figure 5. Melanocytes are found in the Stratum Basale. Cytoplasmic extensions reach into the Stratum Spinosum, though, filled with protein (pigment) molecules as long as the person's DNA is programmed to produce them. The Light skin on the left has the melanocyte, but it is not producing much melanin, or pigment proteins, whereas the Dark skin on the right is forming more of the protein melanin. The Dark skin has melanosome organelles storing the pigments throughout the keratinocytes making the skin appear darker.

CC BY: OpenStax

Acronyms for the layers from superficial to deep, which help us remember the beginning letter(s) of the names of each stratum, include: Can Lucy Give Some Blood? or Corny Lucy's Grandma Spins Baseballs.

The first thing a clinician sees is the skin, and so the examination of the skin should be part of any thorough physical examination. Most skin disorders are relatively benign, but a few, including melanomas, can be fatal if untreated.

Think About This: Which structure in the skin will help you grip a glass? Informs you that the glass is cold or lets you know it's a smooth glass or textured? Read on ...

The papillary layer is composed of loose connective tissue and is vascular. At the upper portion there are dermal papillae (papilla = ridge) that point upwards making ridges, called friction ridges. These papillae create patterns of complex whorls, loops and arches in thick skin that help you grip things and make our unique fingerprints.

The reticular layer is composed of dense irregular connective tissue and is vascular. The vascular dermis supplies epidermis, since it's avascular. Newborns look ruddy because epidermis is thin, so the vascular dermis shows through.

Figure 6. Micrograph of Dermal Layers: The papillary layer with its papillae labeled and the much larger reticular layer are shown.

CC BY: OpenStax College

The subcutaneous or hypodermal tissues insulate, store energy and anchor the skin.The hypodermis is not actually part of the integument but does stabilize skin relative to underlying tissues while allowing lots of movement by skin. In deeper portions there are a limited number of capillaries so it is a good area for injections ("hypodermic" needle), and medicines are absorbed at a slower rate here into the fatty tissue than when injected into muscle (IM).

The skin has several sensory receptors for touch, temperature, stretch and pain, most of which originate in the dermis (Merkel's discs are in the epidermis only). On lab models, you may see free nerve endings (touch, pain, temperature sensations), corpuscles which include Meissner's corpuscles (light pressure) and Pacinian (or lamellated) corpuscles (vibrations and deep pressure, which you could remember by thinking of the "deep Pacific ocean ").

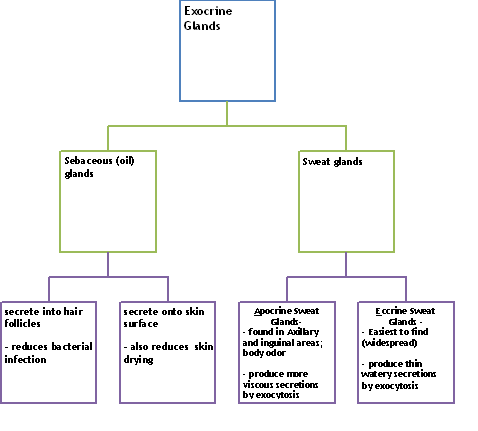

The skin also has glands, including sweat glands, oil (sebaceous) glands, and ceruminous glands in the ear (therefore, ear wax comes from modified sweat glands). Sweat glands (also called sudoriferous glands) are a type of exocrine gland, because their secretions go through a duct to the outside of the body somehow (in this case through a sweat duct to a sweat pore on the surface). There are two kinds of sweat glands: Eccrine and Apocrine. See the graphic below:

The Exocrine Glands

The type of sweat produced in your armpits and groin is usually odorless, but more viscous and smells bad when it combines with bacteria found normally on your skin.

When the sweat evaporates from the skin surface, the body is cooled as body heat is pulled away from the skin surface. In addition to sweating, arterioles in the dermis dilate so that excess heat carried by the blood can dissipate through the skin and into the surrounding environment. This accounts for the skin redness that many people experience when exercising. I know that when I am hot, I can see the superficial veins on my hands as the body sends more blood to my skin surface, but when I am cold, I can barely tell the veins are even there. When body temperatures drop, the arterioles also constrict to minimize heat loss, particularly in the ends of the digits and tip of the nose, which get cold first. This reduced circulation can result in the skin taking on a whitish hue. Although the temperature of the skin drops as a result, passive heat loss is prevented, and internal organs and structures remain warm. If the temperature of the skin drops too much (such as environmental temperatures below freezing), the conservation of body core heat can allow the skin to actually freeze, a condition called frostbite.

An important accessory organ is hair, which helps with touch sensations and protects the body against the harmful effects of the sun and with temperature regulation. It is made of keratin from the hair follicle cells. There are arrector pili (pronounced PI-lee) muscles at the hairs, which raise the hair (traps air for warmth) and causes goosebumps! Hair color is determined by the amount and type of melanin (eumelanin, which is darker and pheomelanin, which is more red).

Sebaceous glands secrete an oily liquid by the holocrine method (whole cells slough off with the oils, so these glands have to have stratified epithelium within them). The oils protect our skin and hair from desiccation. Normally this secretion helps to prevent bacteria from getting into the hair follicle or in to the skin itself. During adolescence, hormones increase and glands increase activity; inflammation or bacterial infection may result, causing acne.

Think About This: There are people who are born without any glands in their skin. Think about how this lack affects their everyday life and what could they do to compensate.

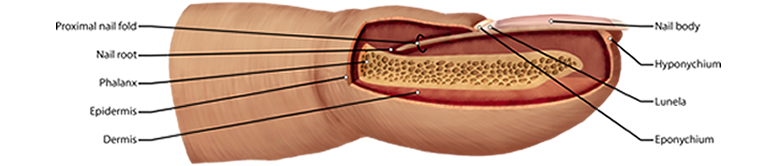

Nails are another accessory organ of the skin. Nails protect the ends of our fingers and toes, preventing infection from getting into the body. The keratinized nail body sits upon the nail bed and grows out from the nail root, all of which are made out of stratified squamous epithelium.

Figure 7. Structures of the Finger: nail, skin, bone. The hardened nail body sits on top of the finger. The lunula is the white half-moon just above the cuticle (eponychium). The distal phalanx bone, which is protected by the nail can be seen as well as the skin's epidermis and dermis.

Show/hide comprehension question...

Keep in mind that even though body piercings and tattoos are popular there are side effects of which to be aware. Since piercings involve needles and expose parts of the inner skin, infections can result (especially with the tongue). Tattoos are unique, however, since they are often laden with metals you should know that MRIs could react with them.

Show/hide comprehension question...

Video 2. Skin Summative Video (opens in a new window).

Except where otherwise noted, this work by The Community College Consortium for Bioscience Credentials is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Text from BioBook licensed under CC BY NC SA and Boundless Biology Open Textbook licensed under CC BY SA.

Other text from OpenStaxCollege licensed under CC BY 3.0. Modified by Alice Rudolph, M.A. for c3bc.

Instructional Design by Courtney A. Harrington, Ph.D., Helen Dollyhite, M.A. and Caroline Smith, M.A. for c3bc.

Media by Brittany Clark, Lucious Oliver, II, John Reece and Antonio Davis for c3bc.

This product was funded by a grant awarded by the U.S. Department of Labor's Employment and Training Administration. The product was created by the grantee and does not necessarily reflect the official position of the U.S. Department of Labor. The Department of Labor makes no guarantees, warranties, or assurances of any kind, express or implied, with respect to such information, including any information on linked sites and including, but not limited to, accuracy of the information or its completeness, timeliness, usefulness, adequacy, continued availability, or ownership.