![]()

![]()

Video 1. View the video Bones- Shapes and Structures on YouTube (opens in new window)

Bone Structure

Bone tissue (osseous tissue) differs greatly from other tissues in the body. Bone is hard and many of its functions depend on that characteristic hardness. Later discussions in this chapter will show that bone is also dynamic in that its shape adjusts to accommodate stresses. This section will examine the gross anatomy of bone first and then move on to its histology.

Gross Anatomy of Bone

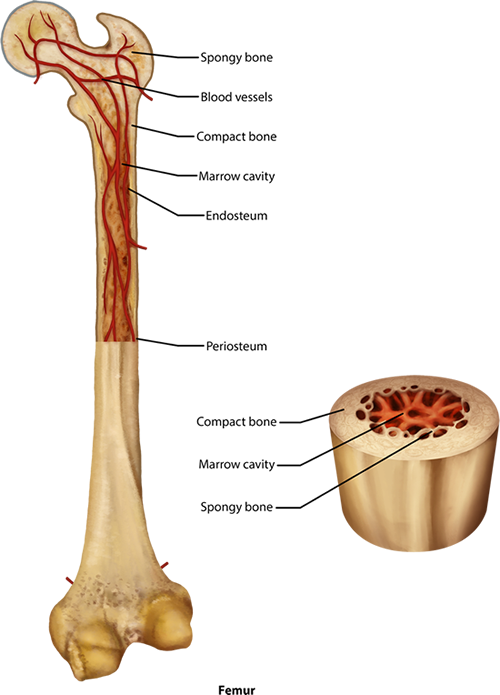

The structure of a long bone allows for the best visualization of all of the parts of a bone (Figure 4). A long bone has two parts: the diaphysis and the epiphysis. The diaphysis is the tubular shaft that runs between the proximal and distal ends of the bone. The hollow region in the diaphysis is called the medullary cavity, which is filled with yellow marrow. The walls of the diaphysis are composed of dense and hard compact bone.

Figure 4. Anatomy of Long Bone. The femur bone here is cut longitudinally in half to reveal the inner marrow cavity of the shaft or diaphysis. The diaphysis contains the compact bone with a thin layer of spongy bone within that is lined with a membrane called the endosteum. At either end there is a head which is filled with spongy bone. Blood vessels run throughout the living bone, and it is covered by a periosteum.

The wider section at each end of the bone is called the epiphysis (plural = epiphyses), which is filled with spongy bone. Red marrow fills the spaces in the spongy bone. Each epiphysis meets the diaphysis at the metaphysis, the narrow area that contains the epiphyseal plate (growth plate), which is a layer of hyaline (transparent) cartilage in a growing bone. When the bone stops growing in early adulthood (approximately 18-21 years), the cartilage is replaced by osseous tissue and the epiphyseal plate becomes an epiphyseal line.

The medullary cavity has a delicate membranous lining called the endosteum (end- = "inside"; oste- = "bone"), where bone growth, repair, and remodeling occur. The outer surface of the bone is covered with a fibrous membrane called the periosteum (peri- = "around" or "surrounding"). The periosteum contains blood vessels, nerves, and lymphatic vessels that nourish compact bone. Tendons and ligaments also attach to bones at the periosteum.The periosteum covers the entire outer surface except where the epiphyses meet other bones to form joints (Figure 5). In this region, the epiphyses are covered with articular cartilage, a thin layer of hyaline cartilage that reduces friction and acts as a shock absorber.

Figure 5. Compact and Spongy Bone. This small section of bone is magnified to show the way compact bone forms osteons in cylinders throughout the length of the bone (this is from the outer part of the shaft as seen in Figure 4). The groups of concentric circles of compact bone, called lamellae, are the osteons that are considered the functional unit of compact bone. Within a central canal of the osteon are capillaries and small veins. These blood vessels came into the bone through perforating canals lying horizontal in the compact bone. In addition to the concentric lamellae, there are also sections of interstitial lamellae seen between the osteons as well as circumferential lamellae that lie beneath the outer periosteal layer.

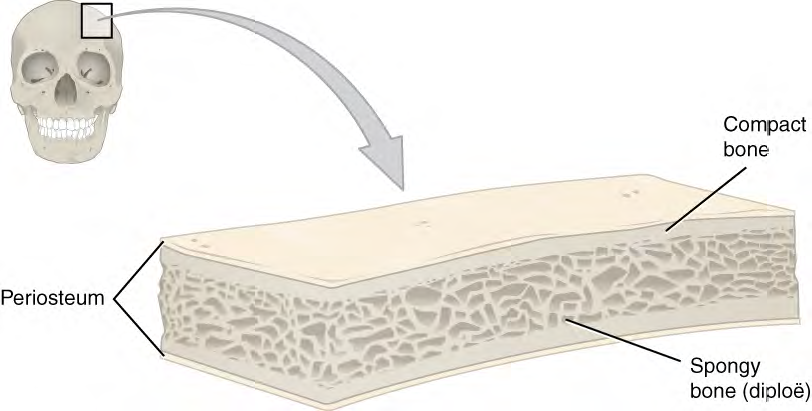

Flat bones, like those of the cranium, consist of a layer of diploe (spongy bone), lined on either side by a layer of compact bone (Figure 6). The two layers of compact bone and the interior spongy bone work together to protect the internal organs. If the outer layer of a cranial bone fractures, the brain is still protected by the intact inner layer.

Figure 6. A cross-section of a flat bone shows the spongy bone on the inside with the compact bone lining it on either side, like a sandwich of spongy, diploe, bone between two layers of compact bone.

CC BY: OpenStax College