Burns

A burn is tissue damage caused by excessive heat, electricity, radioactivity, or chemicals that denature (break down) the proteins in the skin cells. Burns destroy some of the skin's important contributions to homeostasis — protection against microbial invasion, desiccation, thermoregulation, etc. Burns are graded according to their severity.

A first-degree burn damages only through the epidermis (first main layer) like a sunburn.

A second-degree burn destroys the epidermis and part of the dermis causing redness, blister formation, edema, pain, and some skin functions are lost.

A third-degree burn is a full-thickness burn (destroys the epidermis, dermis, and subcutaneous layer). Most skin functions are lost, and the region is numb because sensory nerve endings have been destroyed.

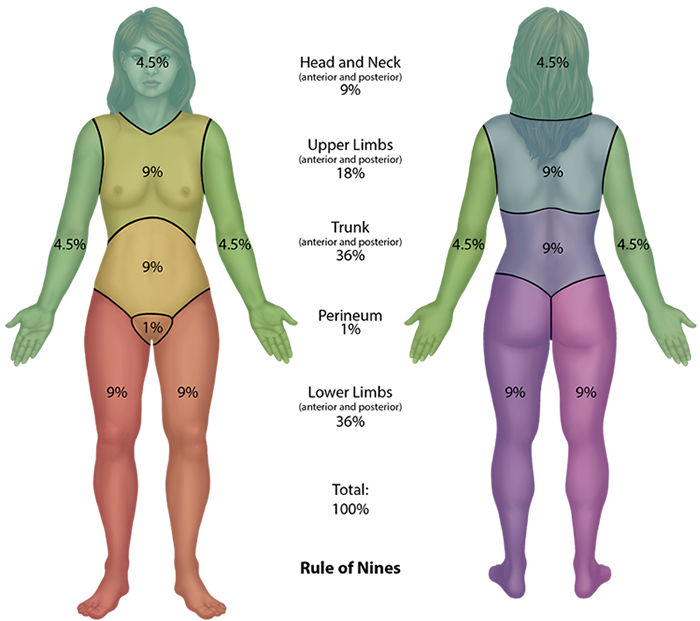

Burns are sometimes measured in terms of the size of the total surface area affected. This is referred to as the "rule of nines," which associates specific anatomical areas with a percentage that is a factor of nine. Each arm is 9% of the body (front and back), the front of each leg is 9%, so each leg is 18%. The torso is a total of 36%. The size of the burn will constitute what the nurse and doctor should do to treat or help the patient, i.e.: the burn victim will need wound care and fluid resuscitation (since risks may include hypovolemia). Destruction of skin layers is usually referred to as a partial-/full-thickness burn, which will require grafting from another area of the patient's body. Depending on the type of burn, often a pressure cuff is worn for a few months after the wound has closed.

Figure 4. Rule of Nines. The body is divided into areas to determine the extent of a burn. The legs are 9% each anteriorly and 9% posteriorly (36% total), the arms are 4.5% each, the back is 18% and the anterior trunk is 18%, the head and neck are 9%, and the perineum covers 1%.

Scars and Keloids

Most cuts or wounds, with the exception of ones that only scratch the surface (the epidermis), lead to scar formation. A scar is collagen-rich skin formed after the process of wound healing that differs from normal skin. Scarring occurs in cases in which there is repair of skin damage, but the skin fails to regenerate the original skin structure. Fibroblasts generate scar tissue in the form of collagen, and the bulk of repair is due to the basket-weave pattern generated by collagen fibers and does not result in regeneration of the typical cellular structure of skin. Instead, the tissue is fibrous in nature and does not allow for the regeneration of accessory structures, such as hair follicles, sweat glands, or sebaceous glands. Scarring of skin after wound healing is a natural process and does not need to be treated further. Sometimes, there is an overproduction of scar tissue, because the process of collagen formation does not stop when the wound is healed; this results in the formation of a raised or hypertrophic scar called a keloid.

Bedsores and Stretch Marks

Skin and its underlying tissue can be affected by excessive pressure. One example of this is called a bedsore. Bedsores, also called decubitis ulcers, are caused by constant, long-term, unrelieved pressure on certain body parts that are bony, reducing blood flow to the area and leading to necrosis (tissue death). Bedsores are most common in elderly patients who have debilitating conditions that cause them to be immobile. Most hospitals and long-term care facilities have the practice of turning the patients every few hours to prevent the incidence of bedsores. If left untreated, bedsores can be fatal if they become infected.

The skin can also be affected by pressure associated with rapid growth. A stretch mark results when the dermis is stretched beyond its limits of elasticity, as the skin stretches to accommodate the excess pressure. Stretch marks usually accompany rapid weight gain during puberty and pregnancy. They initially have a reddish hue, but lighten over time.

Self-Assessment