Objective

- Describe the components and functions of somatic motor pathways.

Continuing on, the sensory stimuli has been received by receptors and relayed to the CNS along ascending pathways. In the cerebral cortex, the initial processing of sensory perception progresses to incorporation of sensory perceptions into memory, and more importantly, they lead to a response. The completion of cortical processing in sensory areas initiates a similar progression of motor processing, usually in different cortical areas.

Prefrontal Lobe

Whereas the sensory cortical areas are located in the occipital, temporal, and parietal lobes, motor functions are largely controlled by the frontal lobe. The most anterior regions of the frontal lobe—the prefrontal areas—are important for executive functions, which are those cognitive functions that lead to goal-directed behaviors. These higher cognitive processes include working memory, which has been called a "mental scratch pad," that can help organize and represent information that is not in the immediate environment. The prefrontal lobe is responsible for aspects of attention, such as inhibiting distracting thoughts and actions so that a person can focus on a goal and direct behavior toward achieving that goal.

The functions of the prefrontal cortex are integral to the personality of an individual, because it is largely responsible for what a person intends to do and how they accomplish those plans. A famous case of damage to the prefrontal cortex is that of Phineas Gage, dating back to 1848. He was a railroad worker who had a metal spike impale his prefrontal cortex (see the figure). He survived the accident, but according to second-hand accounts, his personality changed drastically. Friends described him as no longer acting like himself. Whereas he was a hardworking, amiable man before the accident, he turned into an irritable, temperamental, and lazy man after the accident. The accounts suggest that some aspects of his personality did change. (Later accounts from when he worked as a stage coach driver showed that some of the more sociable aspects of his personality did return.) (credit b: John M. Harlow, MD)

Figure 7: Phineas Gage, 1848, was a railroad worker who had a metal spike impale his prefrontal cortex.

In generating motor responses, the executive functions of the prefrontal cortex will need to initiate actual movements. One way to define the prefrontal area is any region of the frontal lobe that does not elicit movement when electrically stimulated. These are primarily in the anterior part of the frontal lobe. The regions of the frontal lobe that remain are the regions of the cortex that produce movement. The prefrontal areas project into the secondary motor cortices, which include the premotor cortex and the supplemental motor area. Two important regions that assist in planning and coordinating movements are located adjacent to the primary motor cortex. The premotor area aids in controlling movements of the core muscles to maintain posture during movement, whereas the supplemental motor area is hypothesized to be responsible for planning and coordinating movement. The supplemental motor area also manages sequential movements that are based on prior experience (that is, learned movements).

Primary Motor Cortex

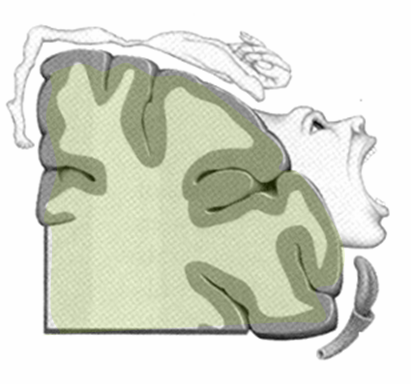

The primary motor cortex is located in the precentral gyrus of the frontal lobe. The primary motor cortex receives input from several areas that aid in planning movement, and its principle output stimulates spinal cord neurons to stimulate skeletal muscle contraction. The primary motor cortex is arranged in a similar fashion to the primary somatosensory cortex, in that it has a topographical map of the body, creating a motor homunculus (see the figure below). The neurons responsible for musculature in the feet and lower legs are in the medial wall of the precentral gyrus, with the thighs, trunk, and shoulder at the crest of the longitudinal fissure. The hand and face are in the lateral face of the gyrus. Also, the relative space allotted for the different regions is exaggerated in muscles that have greater innervation. The greatest amount of cortical space is given to muscles that perform fine, agile movements, such as the muscles of the fingers and the lower face. The "power muscles" that perform coarser movements, such as the buttock and back muscles, occupy much less space on the motor cortex.

Figure 8: The above figure represents the motor homunculus man. Notice the exaggerated structures (hand and mouth). This artistic exaggeration denotes the same concept as the sensory homunculus man but with regards to motor function. The larger or more exaggerated the structure the more motor control over that structure.

Descending Pathways

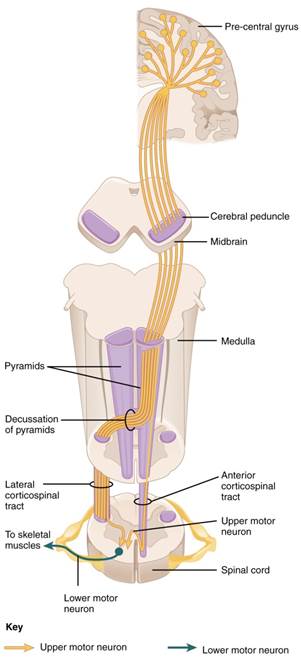

The motor output from the cortex descends into the brain stem and to the spinal cord to control the musculature through motor neurons. Neurons located in the primary motor cortex are large multipolar neurons that extend from the primary motor cortex to the appropriate level in the spinal cord. This one neuron does not leave the CNS, although it does descend the spinal cord, which is why it is termed an upper motor neuron. The two descending pathways travelled by the upper motor neurons are the corticospinal tract and the corticobulbar tract. Both tracts are named for their origin in the cortex and their targets—either the spinal cord or the brain stem (the term "bulbar" refers to the brain stem as the bulb). These two descending pathways are responsible for the conscious or voluntary movements of skeletal muscles. The axons of the corticobulbar tract are ipsilateral, meaning they project from the cortex to the motor nucleus on the same side of the nervous system. Conversely, the axons of the corticospinal tract are largely contralateral, meaning that they cross the midline of the brain stem or spinal cord and synapse on the opposite side of the body. Therefore, the right motor cortex of the cerebrum controls muscles on the left side of the body, and vice versa.

The corticospinal tract descends from the cortex through the deep white matter of the cerebrum. With continued descent, upon entering the medulla, the tracts decussate. At the appropriate level of the spinal cord this upper motor neuron will synapse with lower motor neurons in the ventral grey horn of the spinal cord. The somatic nervous system provides output strictly to skeletal muscles. The lower motor neurons, which are responsible for the contraction of these muscles, are found in the ventral horn of the spinal cord. These large, multipolar neurons have a corona of dendrites surrounding the cell body and an axon that extends out of the ventral horn. This axon travels through the ventral nerve root to join the emerging spinal nerve. The lower motor neuron is also called the terminal neuron because the axon exits the spinal cord and travels to the effector thus stimulating the effector to act and cause a response. The axon is relatively long because it needs to reach muscles in the periphery of the body. The diameters of cell bodies may be on the order of hundreds of micrometers to support the long axon; some axons are a meter in length, such as the lumbar motor neurons that innervate muscles in the first digits of the feet. The axons will also branch to innervate multiple muscle fibers. Together, the motor neuron and all the muscle fibers that it controls make up a motor unit. Motor units vary in size. Some may contain up to 1000 muscle fibers, such as in the quadriceps, or they may only have 10 fibers, such as in an extraocular muscle. The number of muscle fibers that are part of a motor unit corresponds to the precision of control of that muscle. Also, muscles that have finer motor control have more motor units connecting to them, and this requires a larger topographical field in the primary motor cortex. Please see the figure below for a visual representation of the corticospinal tract.

Figure 9: The major descending tract that controls skeletal muscle movements is the corticospinal tract. It is composed of two neurons, the upper motor neuron and the lower motor neuron. The upper motor neuron has its cell body in the primary motor cortex of the frontal lobe and synapses on the lower motor neuron, which is in the ventral horn of the spinal cord and projects to the skeletal muscle in the periphery.

The conscious movement of our muscles is more complicated than simply sending a single command from the precentral gyrus down to the proper motor neurons. During the movement of any body part, our muscles relay information back to the brain, and the brain is constantly sending "revised" instructions back to the muscles. The cerebellum is important in contributing to the motor system because it compares cerebral motor commands with proprioceptive feedback. The corticospinal fibers that project to the ventral horn of the spinal cord have branches that also synapse in the pons, which project to the cerebellum. Also, the proprioceptive sensations of the dorsal column system have a collateral projection to the medulla that projects to the cerebellum. These two streams of information are compared in the cerebellar cortex. Conflicts between the motor commands sent by the cerebrum and body position information provided by the proprioceptors cause the cerebellum to stimulate the midbrain, which sends corrective commands to the spinal cord.

A good example of how the cerebellum corrects cerebral motor commands can be illustrated by walking in water. An original motor command from the cerebrum to walk will result in a highly coordinated set of learned movements. However, in water, the body cannot actually perform a typical walking movement as instructed. The cerebellum can alter the motor command, stimulating the leg muscles to take larger steps to overcome the water resistance.