Objective

- Describe the disorders that affect the sensory, motor and integrative systems.

Adaptation

Now that we are familiar with the process of sensation it is important to address a very important concept, adaptation. Adaptation refers to the decrease in the activity of first order neurons in response to a constant stimulus. What does this mean? When you woke up this morning and were getting dressed you were very conscious of the clothes that you donning. Are they comfortable? Too hot? Too scratchy? Etc. Once you got dressed and headed on to the next part of you day you no longer paid attention to the clothing although the stimulus was still present. It is only when the stimulus changes (shirt gets stuck in a door) or your attention is called to the stimulus (as I just did by mentioning your clothing) that you become consciously aware of the stimulus again. This conscious fading of a stimulus even though the stimulus itself is still present is called adaptation. This process is vital to survival so that the cerebrum can concentrate on the most important task at hand and let the trivial stimuli fade to the background thus prevent perpetual distraction.

This concept of adaptation also illustrates another very important point; not every stimulus that reaches the cerebrum will elicit a response. With limited resources and time to act stimuli are ranked in order of importance and integrated to form a complete picture of the external environment. This allows the brain to respond efficiently to either only the imperative stimulus or to several at one time.

Referred Pain

Though visceral senses are not primarily a part of conscious perception, those sensations sometimes make it to conscious awareness. If a visceral sense is strong enough, it will be perceived. The sensory homunculus—the representation of the body in the primary somatosensory cortex—only has a small region allotted for the perception of internal stimuli. If you swallow a large bolus of food, for instance, you will probably feel the lump of that food as it pushes through your esophagus, or even if your stomach is distended after a large meal. If you inhale especially cold air, you can feel it as it enters your larynx and trachea. These sensations are not the same as feeling high blood pressure or blood sugar levels.

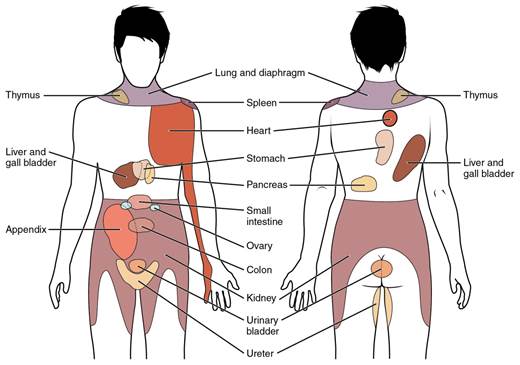

When particularly strong visceral sensations rise to the level of conscious perception, the sensations are often felt in unexpected places. For example, strong visceral sensations of the heart will be felt as pain in the left shoulder and left arm. This irregular pattern of projection of conscious perception of visceral sensations is called referred pain. Depending on the organ system affected, the referred pain will project to different areas of the body (see the figure below). The location of referred pain is not random, but a definitive explanation of the mechanism has not been established. The most broadly accepted theory for this phenomenon is that the visceral sensory fibers enter into the same level of the spinal cord as the somatosensory fibers of the referred pain location. By this explanation, the visceral sensory fibers from the mediastinal region, where the heart is located, would enter the spinal cord at the same level as the spinal nerves from the shoulder and arm, so the brain misinterprets the sensations from the mediastinal region as being from the axillary and brachial regions. Projections from the medial and inferior divisions of the cervical ganglia do enter the spinal cord at the middle to lower cervical levels, which is where the somatosensory fibers enter.

Figure 11: Conscious perception of visceral sensations map to specific regions of the body, as shown in this chart. Some sensations are felt locally, whereas others are perceived as affecting areas that are quite distant from the involved organ. CCBY: OpenStax college

Kehr Sign

Kehr's sign is the presentation of pain in the left shoulder, chest, and neck regions following rupture of the spleen. The spleen is in the upper-left abdominopelvic quadrant, but the pain is more in the shoulder and neck. How can this be?

The incorrect assumption would be that the visceral sensations are coming from the spleen directly. In fact, the visceral fibers are coming from the diaphragm. The nerve connecting to the diaphragm takes a special route. The phrenic nerve is connected to the spinal cord at cervical levels 3 to 5. The motor fibers that make up this nerve are responsible for the muscle contractions that drive ventilation. These fibers have left the spinal cord to enter the phrenic nerve, meaning that spinal cord damage below the mid-cervical level is not fatal by making ventilation impossible. Therefore, the visceral fibers from the diaphragm enter the spinal cord at the same level as the somatosensory fibers from the neck and shoulder.

The diaphragm plays a role in Kehr's sign because the spleen is just inferior to the diaphragm in the upper-left quadrant of the abdominopelvic cavity. When the spleen ruptures, blood spills into this region. The accumulating hemorrhage then puts pressure on the diaphragm. The visceral sensation is actually in the diaphragm, so the referred pain is in a region of the body that corresponds to the diaphragm, not the spleen.